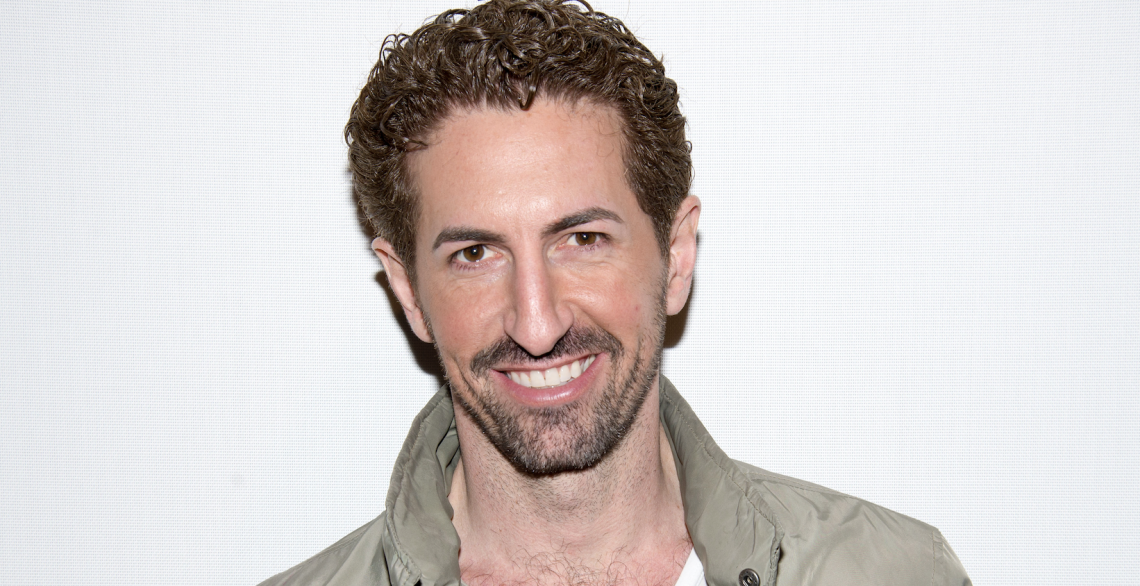

Moran Cerf is a neuroscientist and business professor at the Kellogg School of Management and the neuroscience program at Northwestern University and a member of the Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems. His current research addresses questions pertaining to the neural mechanisms that underlie decision-making and concerns everything from business choices to the launch of nuclear weapons.

Cerf, who holds a PhD in neuroscience from Caltech, an MA in Philosophy, and a BSc in Physics from Tel Aviv University, was recently named one of the “40 leading professors below 40” by “Poets and Quants”. Prior to his academic career, he spent nearly a decade in industry, holding positions in computers security (as a hacker), pharmaceutical, telecom, fashion, software engineering, and innovations research. Cerf is a consultant to the U.S. government and to various Hollywood films and TV shows, such as CBS’ “Bull” and “Limitless” and USA Network’s “Falling Water.” He recently spoke to The Innovator about how business leaders can improve their decision-making skills and why the world needs to rethink its nuclear weapon launch protocols.

Q: What can neuroscience tell us about decision making?

MC: Each brain has its own profile. We can now map your brain and understand in what conditions you make better decisions. For example, some people make better decisions in the morning, others in the evening,;some when hungry, others when they are full; some when presented with a narrow set of options, others when confronted with lots of variables; some when they are close to a deadline, others when they have lots of lead time; some when they are emotional versus calm; some when they are alone, others when they are surrounded by people. The list goes on. We can now figure out your unique profile in the lab by putting a device on your head that measures your brain activity while asking you to play games that manifest your ideal profile. Since not everyone has access to a neuroscientist or neuroscience lab, another option is to do a simplified version of it on your own. You can do this by keeping a diary of every decision you made over a period of, say, ten days and noting the particular conditions you experienced while making the decisions (time of day, who you were with, how stressed you were, etc.). At the end of the ten-day period you would look back and rank the decisions you made as good or bad and try to identify patterns that are manifested when you make the decisions you deem ‘good’. The next step is to try to align your circumstance so that they amplify the good conditions (the people, places, mental state). If you cannot align those, you may opt to outsource some decisions to a person on your team that you trust, and whose mental profile is better equipped for the current choice. Your goal is to promise not to second guess them. It is a way of reducing cognitive load and improving outcomes.

Q: You are currently doing some research for the U.S. government to review the way the decision-making process works for detonating nuclear weapons. Can you tell us how you ended up doing this work?

MC: On Jan. 13, 2018, in Hawaii, at 8:07 a.m. people received a text message from the government that said a ballistic missile has been launched towards Hawaii and advised“Please find shelter.” The assumption was that it was a nuclear missile from North Korean making its way to the island. It turned out to be an error. What struck me at the time was that everyone accepted that this could happen – that a nuclear war can start any time – but then moved on and forgot about it hours later. A few months later, I recalled doing a consulting project, as a neuroscientist, for the U.S. Transportation Security Agency [TSA] to help their employees. Most agents will probably never see a bomb in their life, so the worry was that they might miss it the one time it does pass. That got me thinking about the idea that our brain is flawed. We have trouble thinking about the unimaginable or unlikely. What if we could apply our knowledge about the brain to overcome this and help leaders of countries and CEOs of businesses that need to make critical once-in-a-lifetime decisions improve the way they think about those choices? What if we could apply that knowledge to high-risk-low-probability events such as nuclear protocols or climate crises? I applied for a grant and was immediately rejected because they said that I am not a nuclear protocols expert, and that the probability of nuclear war is negligible so it is not something that needs attention now. So, I decided to learn about the history of the nuclear weapon protocols. When U.S. President Harry Truman was taking office and was handed the nuclear weapons, the military was mostly in charge of it. Truman was told that ‘it is a bigger and stronger bomb’. When the weapons were detonated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki he was horrified. He said ‘this is a weapon to kill women and children’, and said he did not want this weapon in the hands of the military moving forward. He believed it should be put it in the hands of elected civilians so there would be checks and balances. His idea was that one person, the leader of the country, would be responsible and make a calculated and measured response. Today there are nine countries with nuclear weapons. Their leaders include Russia’s Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un and, until recently, Donald Trump. On January 8, 2021, two days after the infamous January 6 events, the U.S. Joint Chief of Staff was so alarmed, he called his counterpart in China and told him ‘I am worried about my boss. If anything happens, please do not start a war. We will do our best to keep it checked here.’ This story was enough of an alarm bell that the U.S. government, along with a consulting arm called the “Nuclear Threats Initiative” came back to us and said ‘we are now happy to rethink your grant.’

Q: Now that you have had a chance to start studying the way things are done what are your takeaways?

MC: We are working on the grant with a non-profit organization and one of the people on the team, Deborah Rosenblum, was designated by Biden to become Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. Part of her job is briefing President Biden on how to prepare for nuclear engagement. I asked her to brief me the same way as she did the President to understand what he learns when he needs to take a decision. It was clear to me that the process does not capitalize on all the knowledge that neuroscientists have about ways to think of critical choices. I started to investigate ways to improve the protocols not just for the U.S. but for all nine countries with nuclear weapons, which have mostly followed the same protocols since they were codified in 1952. I looked at who talks to whom, human biases, and the fact that people might not follow the established cascade of information. As an anecdote, I can tell you that in the U.S., there is a famous large briefcase referred to as ‘the football’ that always travels with the President. People always assume it contains some magical nuclear codes. It does have the authorization codes in it, but mostly, it contains a big book with a lot of military options, as if when the President has 15 minutes to make a critical choice, he or she are going to read through a book. We also have evidence that people regularly violate the protocol’s terms. In the U.S. the President is supposed to attend a meeting once every quarter that is effectively a ‘war game’ with the clock running, where they get to experience the situation and rehearse the protocol. The last U.S. President to attend these rehearsals was Jimmy Carter. Another example is 9/11. Then U.S. President George Bush was reading a story to kids – “The Pet Goat” – when his chief of staff learned about the attack in New York City and whispered in his ear: “Mr. President America is under attack.” This could have been a nuclear attack, the same words would have been used if it was a nuclear one, and the protocol is very clear about the fact that there is a countdown of minutes to take a decision in these moments. Yet, Bush (in what I think was the correct move) chose not to convey panic. He stayed in his chair and finished reading The Pet Goat for six of the next minutes, cannibalizing some of the critical minutes the protocol speaks about. This tells us that the protocols are not only flawed, they also may not be followed in times of crisis. The war in Ukraine and a lot of things that have happened in the past 12 months have brought a renewed urgency to reviewing how these decisions are made. There is talk of ‘mini nukes’ or ‘tactical nukes’ which are ways to normalize the fact that nuclear weapons might be used. To be clear, a mini nuke could easily be equal to the bomb that was detonated in Nagasaki. We now have nine countries with these weapons and other countries are starting to talk about acquiring them, escalating the risk. The risks are certainly amplified.

Q: What can be done to improve the current process?

MC: A lot. The conditions that the protocols operate under are almost inducive of mistakes and biases. The time pressure, the single point of failure, the strict chain of command, the fact that the decision is made under stressful emotional states. All of those are terrible states to take decisions in.

A colleague of mine ran a study at the Munich Defense conference a couple of years ago. Participants took the position of President of the U.S., and were told that within 15 minutes ballistic missiles from an unknown source might hit the U.S. They were told ‘you have 15 minutes to decide what to do’. Participants could ask questions, but the answers were intentionally all vague and ambiguous. Out of about 200 security experts in the study the majority chose to launch a nuclear strike in less than the allotted time. One of the participants said: ‘My job is to think about nuclear security, and I have been advocating for the opposite response all of my life’, after she authorized a nuclear strike. The message is the current protocol is very prone to human errors and biases. For example, the fact that you need to respond very fast, or that not doing anything seems like a mistake are challenges. Some countries tried to solve it by changing those conditions. Israel, for example, has changed the time limitation. Other countries separate the warheads from the missiles to force a mechanical delay. If other countries changed the time allocations and introduced the notion that it is ok to wait and make sure you are correct before you launch it would already be a game changer. Second, having a protocol that is geared towards a decision often favors an action over no action. We give people rewards for action. We need to change the incentives so that ‘not doing anything’ would be rewarded.

We also need to think more about the influence of rehearsal and repetition on thinking and the likelihood to align prior actions with future outcomes. Specifically, the fact that you tried something before, and it worked, makes it more likely you will favor it in the future. This is the reason some countries avoid some training, to ensure that prior decisions do not influence thinking. France, for example, made a conscious choice to not have the leaders participate in various war games rehearsals because it does not want the people in the room to know how the leaders think, and they do not want the leader to succumb to inertia in how he or she responds to certain scenarios.

Other recommendations have to do with the chain of command. The gist is that the cascade of instructions impacts the outcomes. If the five people immediately below the President all say ‘yes’ to a certain action then it is harder for the sixth person to say ‘no’. It is also typically harder for people down the chain of command to fully contradict a more senior person’s opinion once it is publicly stated. If it is important for a leader to hear all the opinions and give people in the room a chance to vote, then anonymous decision-making protocols are favorable as a first step in the evaluation of options. Following those with a transparent decision gives people a chance to calibrate their view before the actual vote occurs. I also believe that the protocols need to be updated with every new leader to ensure they optimize that person’s approach to decision-making. Some leaders respond better to information presented visually; others prefer to see information as comparative analysis. To ensure maximal accuracy learning how people understand data and making sure they get the data in a form that aligns with their perception is another recommendation we had.

Q: How can some of this learning be applied to business?

MC: Generally, thinking about who speaks when (i.e., should the boss speak first, or let his/her subordinate express their opinions early) matters. Asking questions rather than stating opinions – especially by senior people who interact with others – helps create an environment of exchange rather than giving orders. Taking a break after all the opinions are expressed and before the final ‘thumbs up/down’ is useful. Be aware of the fact that our brains like to have consistency, often at the expense of accuracy. Simply put, many people feel that arguing for an opinion and then fully changing their mind is somehow a ‘flaw’ and have a hard time doing it. Practicing rethinking our own opinions is very healthy when taking critical decisions. Often, assigning a person/team to be the ‘red team’ – the team that is tasked with attempting to find flaws in the decision or challenging it – helps a lot in striving towards a good outcome. Assigning someone to be the ‘opposition’ in advance removes the discomfort of having the ‘guts’ to do it. Another recommendation would be to reward no action as in, ‘after a lot of thoughts we decided not to do anything’. It makes people realize that deliberation that leads to no action is a constructive outcome. Finally, I would say that an extremely useful thing to do is have a culture of post-mortem evaluation of choices. As in, after every critical decision/action it is useful to have the people involved sit together, calmly, when things have settled, and opine on the choice process: what they liked, what worked, what could have been improved and whether they agree with the outcome or still oppose it. Those actions, which are very common in the military, help perfect the process over time and are invaluable.

This article is content that would normally only be available to subscribers. Sign up for a four-week free trial to see what you have been missing.

To read more of The Innovator’s Interview Of The Week stories click here.