When an executive from global appliance maker BSH watched a Silicon Valley-based start-up’s augmented reality demo at a trade show in China it sparked an idea. What if the same technology could be used to project images of food inside the appliance makers’ ovens and refrigerators to dazzle visitors during the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas?

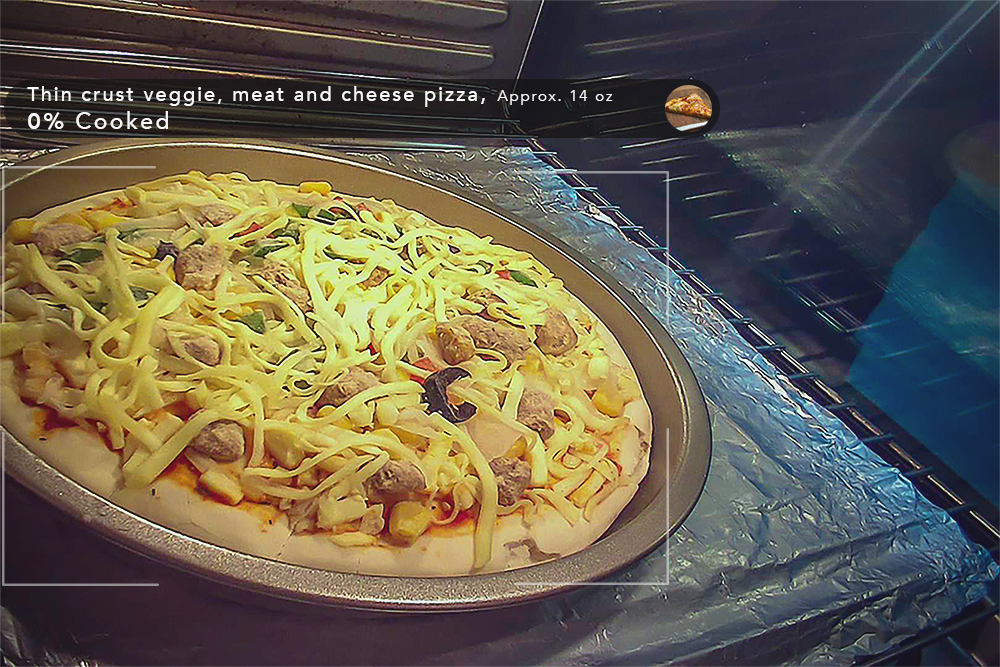

Up until then Passio’s computer vision and edge-AI technology was only being used to analyze food on a plate for nutrition intelligence But after being contacted by BSH Startup Kitchen, BSH’s startup partnering unit, Passio shortened its development cycle and found a way to use its tech to project some 30 foods into a fridge or an oven (see the picture). The deal with BSH was concluded and the product developed in just a few months, in time for the trade show.

Passio’s story is just one example of how BSH Startup Kitchen’s dedicated fast track is helping it discover and adopt solutions from startups throughout the world. The objective of this unit is to integrate the latest innovations into the appliance maker’s products, services and processes quickly and efficiently, says Munich-based BSH Startup Kitchen Venture Partner Ion Hauer.

It’s part of a trend. A growing number of large corporates are moving away from accelerators. “We closed ours down,” says Hauer. Instead of working with Techstars, BSH Startup Kitchen has adopted a startup partnering model, which Hauer calls a form of intelligent procurement. “We pay startups like suppliers for their products and solution and don’t invest,” he says. “It is a very clean model.” One, he says, that has turned out to be a recipe for success.

Using this model, BSH Startup Kitchen has connected with startups that have helped solve specific problems. A proof-of-concept trial phase usually lasts two to four months. The startup is paid for the trial so there is “skin in the game and mutual commitment,” says Hauer.

To help ramp up the process the appliance maker decided not to leave its sourcing of startups to chance. It has partnered with GlassDollar, a German company that helps corporates source, manage and scale startup collaborations. In addition to BSH, GlassDollar is working with Siemens, Daimler, Henkel, Telefonica and Miele, among others.

“In the past year and a half more than half of German DAX companies have officially adopted the startup partnering model,” says GlassDollar CEO Fabian Dudek. GlassDollar provides a number of services: It enables corporates to start or scale their startup partnering unit and provides startup sourcing, project management, legal structure for a fast-track process and systematic impact tracking. “Some companies have anywhere from 20 to 50 proof of concept trials going on at the same time and they need an infrastructure to manage that,” says Dudek. “We can provide them with an out-of-the box software solution and the legal infrastructure that helps them to run projects faster as well as measure the business impact.”

In GlassDollar’s recently published ranking of the “most innovative companies in Europe 2021” Siemens ranked number one, with 167 disclosed startup collaborations. Bosch, which owns BSH, ranked third with 97.

GlassDollar is using the ranking to help startups identify which corporations are the best partner or customer; which startups leading corporations have already partnered with; understand current macro innovation trends; and convince them that startup partnering relationships with corporates makes economic sense. “We have enabled more than €50 million in revenue for startups, and we think we can very quickly increase that to €500 million or more,” says Dudek.

Germany’s Micropsi Industries, a seven-year-old robotic software company that has developed a solution that marries AI and industrial robotics to tackle variance in production, was skeptical at first but says it is now convinced by the model. The majority of corporate interfaces built specifically to deal with startups “don’t work,” says CEO Ronnie Vuine. Micropsi “doesn’t want pizza or to be part of a hackathon. We are grown-ups with a product that is ready to be integrated into production lines and we want to be paid properly and treated like any other supplier.”

Most of the people in charge of innovation have no power within big corporates, says Vuine. The problem is so bad “that we had reached the point that we do not talk to corporate innovation managers because it will just be about that person ticking some box and we won’t sell any product,” he says.

BSH Startup Kitchen proved to be the exception, says Vuine. It first approached Micropsi with a problem that the German startup could not solve. “We were super honest about it and BSH Startup Kitchen said ‘fine, let’s find another use case, found the right people and arranged a meeting,” says Vuine. The meeting led to the purchase of one of Micropsi’s units by a BSH factory in Spain. “Now we can prove that what we are promising to them is possible,” says Vuine. “And we know they are serious. We are working together. They are a customer, and we are their supplier. There is nothing specific about this that is tied to being a startup. We got paid and now we are ready to fight for the next tender.”

Fluent.ai, a Montreal-based company that has developed speech-to-intent technology that uses neural networks to directly map a user’s speech to intended action, was also able to get its product onto the production line via BSH Startup Kitchen. Its technology, which is embedded in consumer devices, can also be used by assembly line workers to speed production. “BSH Startup Kitchen makes collaboration work,” says Kirsten Joe, Fluent.ai’s vice-president of sales and marketing. Last year the venture client program arranged three pitching sessions for Fluent.ai. It has since moved from one factory assembly line pilot to three and BSH is considering using the technology at other factories both inside and outside of Germany, she says. “Having a dedicated contact person makes a key difference,” says Joe. “Seeing your solution working in the real world is what it is all about. BSH Startup Kitchen is able to prioritize pilots and expediate their move onto the factory floor.”

That said, the process is not frictionless for all startups. Mavenoid, a Swedish startup that has developed an AI-powered platform for technical support that enables companies to automate repetitive support issues and empower service teams, said it was able to get sign-off for a pilot project within just two months. “This was exceptionally fast for a company the size of BSH,” says Tilda Sander, Mavenoid’s head of growth and partnerships. But the company’s deal with BSH is still limited to its UK website. “So many people need to get involved; we have struggled to get a widespread commercial agreement,” she says.

Still, compared to many large corporates, all four startups interviewed said BSH Startup Kitchen deserves high marks. “Many enterprises do not have a process for working with small companies on product development: they don’t know how to deal with skunk works and there are no rules of engagement,” says David Westendorf, co-founder and chief operating officer at Passio. “The fact that BSH has a department that is focused on the startup world and acts as a clearing house is already a major breakthrough.” He also highly rates BSH Startup Kitchen for the way it organizes its Startup Days. Westendorf said he traveled to Germany from San Francisco for one such event in December of 2019. “There were seven product managers lined up to see our demo,” he says. “I’ve never had that in my life. I would usually have to take seven flights to arrange these meetings. If every company would follow this model startups would be in a much better place.”

This article is content that would normally only be available to subscribers. Sign up for a four-week free trial to see what you have been missing.