Klöckner & Co., one of the largest producer-independent distributors of steel and metal products worldwide, is not the first company that comes to mind when thinking about digital pioneers even though the 113-year-old German group has arguably earned that moniker.

It is among the first traditional business-to-business (B2B) companies in Europe to adapt the platform business model popularized by Internet giants.

Platform business models create ecosystems that attract, match and connect different groups across the globe and enable them to interact. Unlike traditional linear value chains, in platform models value is distributed across a dynamic network of customers, suppliers and competitors, creating a network effect that has allowed new businesses to grow at an unprecedented rate. Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent are all examples of companies that have done just that . They have grown exponentially by placing themselves at the center of ecosystems.

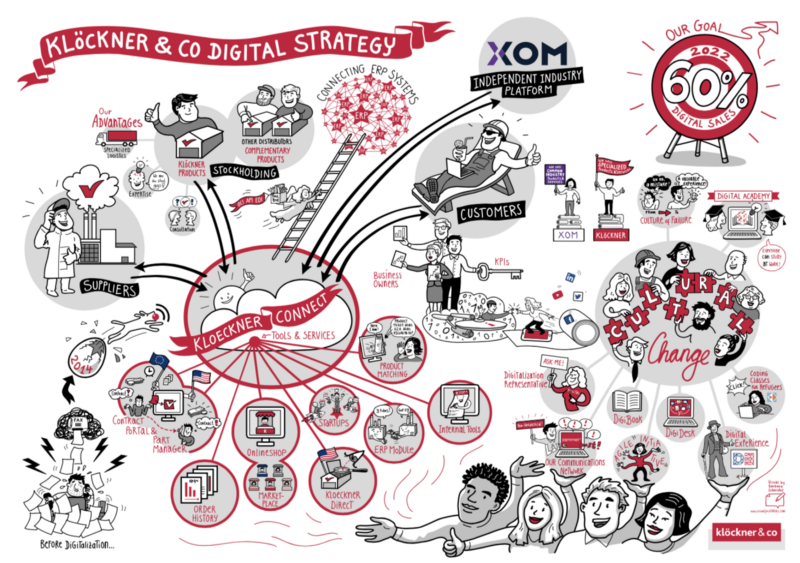

Klöckner, which has a distribution and service network of about 170 locations in 13 countries supplying around 130,000 customers, began fully digitizing its supply and service chain five years ago. Online transactions already contribute 23% of the group’s €6 billion 2017 sales revenues. The goal is to shift a total of 60% of its business to digital in the next three years. It has separately created an independent open industry platform called XOM Materials which it hopes will become the dominant global ecosystem not just for steel and metal but also neighboring industries that supply materials to the construction industry: think cement, screws or even plastics.

Gisbert Rühl, the company’s CEO, says he was first sold on the concept of going digital following a visit to Silicon Valley in 2014. While the first generation of large Internet platforms disrupted digitizable services like music, the second generation of so-called online to offline, or O2O, platforms covered wide-ranging groups of consumer-driven industries like urban transportation (Uber and Lyft), lodging (Airbnb) and food delivery (Just Eat and Delivery Hero). Rühl’s light bulb moment came when he realized that the same fundamentals that drive consumer 020 platforms can also be applied to goods and services that companies trade with each other.

The key takeaway was that “platforms will become the dominant business model of the 21st century, not only in B2C but also in B2B,”says Rühl.

Faced with pressure on margins and convinced that platforms would define the future, Rühl set about the difficult business of transforming not only his company but also the way the entire steel distribution industry works. His reasoning? If Klöckner didn’t do it someone else would.

Rühl’s insight has proved to be prescient: After successfully disrupting numerous traditional industries with its platform approach Amazon now sells industrial-grade steel online.

Klöckner is one of over 50 large corporations such as Henkel, Schneider Electric, Deutsche Bank and General Electric that are participating in the Digital Platforms & Ecosystems working group, part of the World Economic Forum’s Digital Economy and Society system initiative. All are grappling with how to best apply the platform business model to traditional industries. B2B platforms could represent $10 trillion in socio-economic value creation from 2016 to 2025, according to an Accenture report compiled in partnership with the World Economic Forum. The report notes that this estimate — derived from a larger forecast which estimates $100 trillion of value is at stake through 2025 — may, in fact, be conservative. Separate independent research confirms that more than 30% of global corporate revenue will come from digital platforms by 2025, and yet only 3% of established companies have adopted an active platform strategy.

Klöckner’s transformation holds important lessons for other B2B companies, says Cristian Citu, Digital Transformation Lead at the Forum. “There is obviously no silver bullet when it comes to adopting the digital platform business model, but there are certainly strong lessons to be taken from Klöckner,” says Citu. “t is impressive to observe the way the organization learned from a first attempt to build their own web shop, and then launched a very successful separate digital platform which has evolved into a cross-industry platform.”

A Sector In Crisis

Klöckner has long played an important role in the steel industry value chain. Only customers that buy huge amounts of steel can order directly from mills and delivery can take up to three months. The German distributer buys steel from big mills, which it stores in some 170 warehouses around the world in order to efficiently serve local markets. Its customers include construction companies and automakers as well as craftsmen who want to buy small amounts of steel and for delivery within as little as 24 hours.

But demand for steel in Europe fell 20% after the 2009 global financial crisis but production remained the same, leading to huge overcapacity. Steel from China also flooded the European and U.S. markets, putting margins under pressure. This forced Klöckner to reduce its workforce from 11,700 to 8,700 and close a number of warehouses in Europe. “It was clear that the company needed to find growth and just closing unprofitable sites could not be the only solution,” says Christian Pokropp, a Klöckner managing director. “We saw digitalization as a chance to differentiate ourselves and also to spur new growth.”

Getting started proved tougher than imagined. “We set up an internal group to develop innovation for our industry but it soon turned out we were not innovative enough,” says Pokropp. “Every time someone came up with a new idea someone else thought of a reason why it should be killed. After a few weeks we realized this was the wrong approach and stopped this group.”

An outside advisor was hired who presented ideas that could make it easier for Klöckner to collaborate with its clients — basing its suggestions on interviews with customers. “This customer-focused approach fascinated our CEO,” says Pokropp. It led to a decision by the company to ask two management trainees to rent workspace at betahaus, a Berlin-based co-working space and community of 500+ entrepreneurs and freelancers. Their mission? Find out if startups would be interested in working with Klöckner on a customer-focused digital strategy. Interest was “extremely high because bringing the steel industry online was better for startups than starting the fifth online shop for pet food,” says Pokropp. “The potential for B2B marketplaces is far bigger.”

With the help of some local startup talent the group created a separate company, called klöckner.i, in Dec. 2014, and launched an online marketplace for Klöckner’s steel customers. “This was really a revolution for the steel business,” says Pokropp, a member of the board of klöckner.i. “Before we did this prices were not transparent and most orders were sent by fax. Now our clients can order steel via their smart phones. It is way more comfortable for them.” klöckner.i also created a service that gives customers an overview of all of the contracts it has with the company.

“We got very positive feedback from our customers but we needed to convince our sales people,” says Pokropp. “When all the digitalization initiatives started there was fear that we would further reduce our workforce. We completely changed our internal communications in order to convince and educate our people.”

It took several initiatives, the use of digital communication tools and several years to foster the right cultural change. Along the way a decision was made to create stronger ties between Berlin-based klöckner.i and the parent company in Duisberg. “We found our people in Berlin really needed knowledge of the traditional business in order to sell steel online,” says Pokropp. “And people from the traditional business really need to understand what the people in Berlin are doing so they can contribute to our future success.”

Klöckner employees from all over the world are regularly sent to work in the Berlin digitalization unit for two months, spending 50% of their working time helping further the group’s digital strategy. Some of them act as digital ambassadors when they are sent back to their business units. Klöckner has also launched a digital academy that offers online courses about e-business. More than 1,100 employees have already signed up, says Pokropp. Managers are also expected to have a basic knowledge of coding and take classes that expose them to startup thinking, such as agile working and launching minimally viable products.

“The most difficult part of the digital transformation is the cultural change that accompanies it,” says Rühl, “to convince your own employees and customers of the benefits of digital distribution channels and inspire them to embrace new forms of cooperation.”

The Move To Open Marketplaces

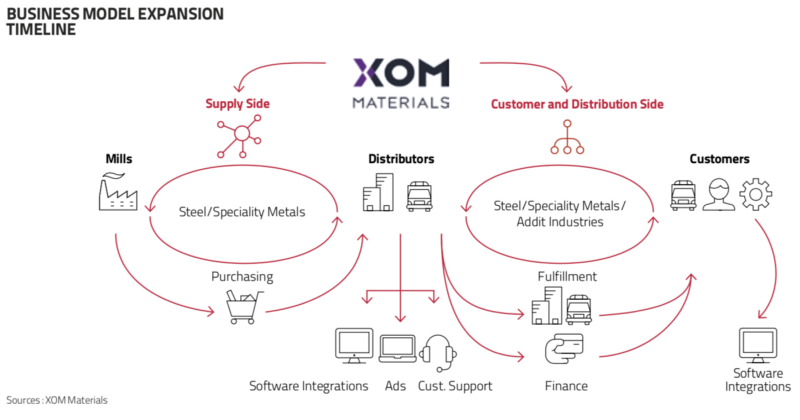

In 2018 the company opened up its marketplaces: first creating a digital platform for third-party sellers, like distributors who offer complimentary products such as a steel grade that Klöckner does not have in its portfolio, so that it could offer customers a wider range of products, and then creating a spin-off called XOM Materials, the completely independent industry platform that was launched in Feb. 2018. Ten distributors, including some of Klöckner’s direct competitors, are live on the XOM Materials platform and about 100 customers have registered. The platform is focused on commodity products that are sold in large volume while the Klöckner online shop and marketplace sells more specialized products in smaller amounts.

“Many of our products require specialized logistics,” says Pokropp. “These cannot be offered by Amazon but this might change in the future so we have to grow our marketplace as soon as possible.”

The idea behind XOM Materials is to create an open ecosystem that enables transactions among all market participants: steel mills, distributors — including competitors — and customers. The expected benefits for customers are efficiency gains, better pricing conditions due to higher transparency, faster delivery times due to network-enforced demand matching, and faster purchase realization cycles.

XOM Materials also offers advantages to small- and medium-sized distributors, allowing them to access larger customer bases by taking advantage of platform services such as fulfillment and finance. It also aims to cut distributors’ costs through better demand forecasting. Suppliers and producers are expected to benefit by becoming less dependent on distributor networks and partnerships.

The XOM Materials network is being built step by step. It is first targeting small- and medium-sized distributors, then large distributors and eventually the supply side, i.e. large steel mills. The total addressable steel market in the U.S. and Europe alone is €250 billion. But Klöckner doesn’t expect to stop there. It is already selling plastic parts into the construction industry, prompting XOM to change its name to XOM Materials.

“The race for the market shares of the future is being decided today,” says Rühl, the company CEO. “The digitization of existing offline processes is not enough to be one of the winners. Rather, it is about creating disruptive business models such as platforms. With our industry know-how and digital competencies, we have a good chance of playing a decisive role in the platform business of the steel industry and adjacent sectors.”[CP5] “