Smart factories have the potential to add $500 billion to $1.5 trillion in value to the global economy within five years. The World Economic Forum wants to help manufacturers and governments seize the opportunity.

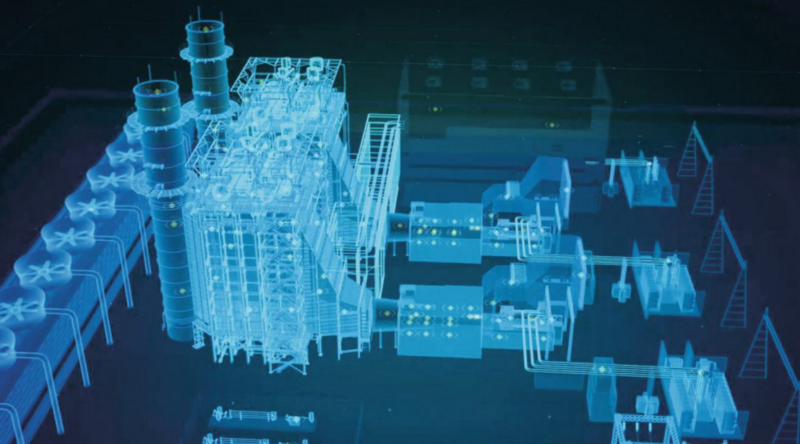

The manufacturing industry appears to be next in line for massive disruption. Historically, operating efficiency in manufacturing has come through specialization, scale, and repetitive task robots. The factory of the future will operate much differently: it will use advances in robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), material science, 3D printing, and the Internet of Things to allow every object in a factory to communicate with the others, and directions for assembly to be made at the product level rather than a central hub. This will help reduce the cost of making customized items to be on par with the cost of mass production and offering a host of other advantages.

AI is well suited to addressing the challenges facing manufacturing, such as variable quality and yield, inflexible production line design, inability to manage capacity, and rising production costs, argues Andrew Ng, a former head of AI initiatives at the Internet giants Google and Baidu. AI can help tackle these issues, and improve quality control, shorten design cycles, remove supply-chain bottlenecks, reduce materials and energy waste, and improve production yields, says Ng, who has launched a new company, Landing.ai, to help manufacturers harness AI. However many manufacturers are proceeding with caution due to concern over widespread job losses, the digital skills gap and an escalation of cyber attacks on factories once the use of the Industrial Internet of Things becomes widespread.

In fact, a new study by The World Economy Forum and AJ Kearney found that no country has reached the frontier of readiness, let alone harnessed the full potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in production. While there are early leaders to learn from, these countries are also still navigating the early stages of transformation. That’s why “Shaping the Future of Production” is on the agenda at the Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, January 23–26. The Forum officially launched this as a project area in early 2017, an offshoot of other work it was doing related to manufacturing economies. “If you’re really going to make this work, we’ve got to go further and faster,” says Helena Leurent, head of government engagement and future of production at the Forum.

At the annual meeting the project’s goal is to explore ways to bridge both the gap between national governments, who are setting their own industrial policies, and the divide between governments and industry. Given that many manufacturing businesses cross borders, having greater alignment between these actors could go a long way to jumpstarting this transformation, Leurent says.

Productivity Gains

The potential gains from the adoption of new technologies in manufacturing are seductive for both governments and industry. In a July 2017 Capgemini report, the consulting firm estimates that manufacturers who fully embrace these new technologies will see a seven-fold increase in productivity by 2022. And, Capgemini projects that smart factories have the potential to add $500 billion to $1.5 trillion in value to the global economy within five years.“AI has the potential to pave the way for manufacturing to power a new generation of productions, devices and experiences,”says Ng. “Bringing AI to manufacturing will also help revitalize manufacturing jobs in the U.S. and globally.”

Ng’s company, Landing.ai, signed a partnership with Foxconn last July to develop “AI technologies, talent and systems that build on the core competencies of the two companies.” Their stated aim is to help manufacturers who lack expertise in new fields like AI and find it difficult to build their own teams in-house given the broader competition for talent. The Capgemini report notes that while 76% of manufacturers either have a smart factory project or are developing one, only 14% are satisfied with their level of smart factory success. And only 6% have reached an advanced stage of actually implementing these technologies.

Greg Mulholland, founder and CEO of Citrine Informatics, a World Economic Forum 2017 Technology Pioneer, knows how hard it can be for industrial partners to embrace radical new methods. Founded in 2013 and based in the heart of Silicon Valley, Citrine Informatics draws on big data and AI to bring new efficiencies to the process of creating new materials for products. Traditionally, material science has used the classic scientific method approach to create breakthrough substances that in turn enable new products, says Mulholland. But increasingly, product makers are demanding new forms, particularly for things like consumer electronics, every 18 months to two years. Citrine uses a wide range of data from external sources such as research databases and internal data from a company’s manufacturing system to accelerate the development of new materials. But to really leverage that service, ideally clients need to have their factories equipped with as many sensors and data-gathering points as possible. Making those physical changes can be slow going, and requires bringing together many other technologies.

“Most companies don’t have a systemized data structure built with AI in mind,” Mulholland says. “We really need to provide a data platform that allows them to capture their data and make it useful. When I think about how the world is going to change I have a very clear view of how these things are going to come together. And the ones that are best at integrating them are going to have a major advantage.”

Optimizing Data

Located not far from Citrine Informatics in Palo Alto, California is Maana, a company founded in 2012 that is also trying to help manufacturers leap into the future. Maana, another of the Forum’s Technology Pioneers, has developed a kind of industrial search engine to help factories optimize the use of the data they collect once they’ve gathered it. Maana co-founder and CEO, Babur Ozden says companies are eager to try these solutions because productivity gains have slowed in recent years. Many are anxious about being left behind as they see competitors with huge resources, like GE or Airbus, investing and starting to reap some benefits. “The companies and the governments that can adopt these new technologies are showing significant benefits that are not incremental, but are radically different,” Ozden says.

3D Printing

Take the case of 3D printing, a customizable means of production, which has the potential to drastically reduce material costs, shrink supply chains, improve product performance, and increase design freedom in multiple industries, says the research firm CB Insights. GE is the dominant player in the space, with six equity investments since 2013 through GE Ventures, three acquisitions, a dedicated additive manufacturing division, and multiple 3Dprintedpartsinservice,accordingtoCBInsights’data.BMW,alongwith its venture arm, has invested in the World Economic Forum Technology Pioneer Desktop Metal, as well as in Carbon and Xometry. It has used 3D printing in prototyping and tooling for decades, and introduced 3D printed parts into series production in 2012. Siemens has invested in Markforged and acquired Material Solutions through its next47 fund. The German industrial conglomerate uses additive manufacturing throughout its businesses, including a 3D-printed gas turbine blade.

That said, in addition to issues like talent and strategy, Leurent says the very nature of how companies experiment with new technologies is often problematic. For instance, pilot projects can take longer than expected, and might not reveal benefits because they are too small in scale. In addition, many of these technologies remain far out of reach for medium and small businesses. And governments and employees understandably worry that productivity gains from Industry 4.0 become job killers rather than job creators. What’s more the Forum’s new Readiness for the Future of Production Report 2018, found that 90% of of the countries from Latin America, Middle East, Africa and Eurasia included in the assessment have a low level of readiness, so there is a danger of creating a two-speed world. At the annual meeting, Leurent wants participants to help tackle these challenges. Topics on the table include: Could an industry or coalition of countries create a network of test centers to help smaller manufacturers? How can countries draft the right regulations to encourage adoption? How can employees be trained or re-trained to have the necessary skills? And what kind of sustainability goals and programs can help limit environmental impacts?

“It’s not enough to be doing this on a piecemeal basis,” says Leurent . “We know the shift is coming. As we go through a period of great changes, we could, if we shape the right conversation, change the productivity paradigm. The challenge is how to look at the opportunity and lean into it, rather than letting the technology drive us.”