— Progress has been slow, but Europe may have a chance to lead by offering an alternative form of AI.

As the U.S. and China vie for supremacy in the global artificial intelligence (AI) race, Europe risks being left behind. The European Union is home to some of the world’s best universities and coders and has long emphasized the deep math that underpins AI. But progress is being hampered by slow decision-making, too little investment in AI by Europe’s private sector and bureaucratic procedures in the public sector, an emphasis on separate national AI strategies, no sense of urgency and too little prototyping. Some of its best AI experts are now running AI operations for Facebook and other Silicon Valley companies and some of its most successful AI companies — such as DeepMind — have been snapped up by the likes of Google. And venture capital is flowing elsewhere: In 2017, according to the Joint European Disruption Initiative (JEDI),

48% of VC investments in AI went to China, 38% to the U.S. and 14% to the rest of the world including, among others, the EU. But a group of respected policy makers, academics, investors and entrepreneurs say they believe Europe has a chance to lead by offering an alternative form of AI — one that safeguards European values such as data privacy and democracy, by hardwiring them into the technology. Such an approach addresses growing concerns about the way data privacy is handled by Silicon Valley companies. The Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal brought the issue front and center. The firm is accused of using data it improperly obtained from Facebook to build voter profiles and influence the U.S. presidential election. At the same time, China’s use of AI-powered surveillance technology to control its population is creating unease in the West.

Carlos Moedas, the European Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation and a co-chair of the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting of The New Champions in Tianjin, confirmed to The Innovator that the EU is considering hardwiring ethics into AI. “The recently launched High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence is looking into this, working closely with a broad range of stakeholders through the European AI Alliance,” says Moedas. “Beyond privacy, ethics by design is also on the agenda, as well as possible certification and standardization procedures.”

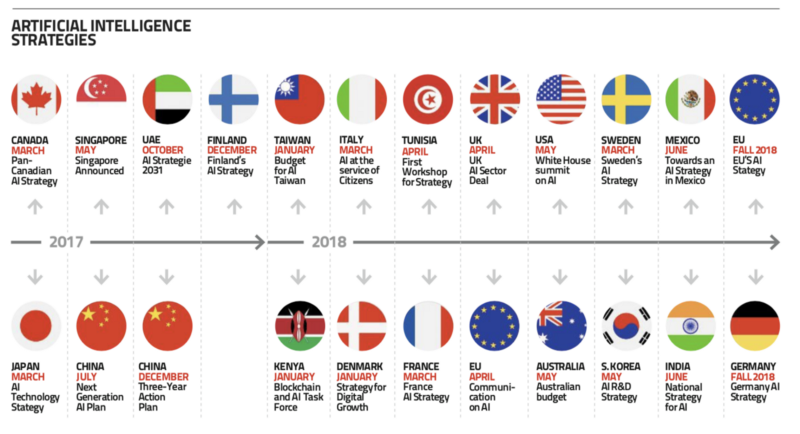

Credit: Politics +AI, Tim Dutton

Embodying Ethics

Françoise Soulié, a member of the EU’s High-Level Expert Group on AI who has over 40 years’ experience working with neural networks, machine learning, social network analysis and Big Data in academia and in industry, is pushing for Europe to take that approach. She is a co-founder of Hub France Intelligence Artificielle, a French organization that aims — through a bottom-up approach — to help create an AI industrial sector in France and Europe.

“To me it is very important that Europe has an offer — not just a law — an offer of technical products that embody ethics in them, ethics as a design principle,” says Soulié. “This is going to be a competitive advantage. The European mark will say ‘these projects can be trusted’ — and they are going to be on the market side by side with American and Chinese products without that label. The Commission has put that on their list. For me it is not about legal issues only. We need products with ethics in them. The question is how can we develop norms so a product would have a kind of International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard stamp. This is what I intend to push.”

Europe could be a global leader in ethical AI, agrees Charlotte Stix, a policy officer and research associate on AI policy at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge. “The European Commission’s recent documents, as well as national policy reports and legislation such as the GDPR [Europe’s new stricter data protection law] point towards that direction,” says Stix, who formerly worked at the European Commission’s Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Unit, where she oversaw a total of €18 million in Robotics and AI projects and contributed to the formulation of EU-wide AI strategy.

The problem is that the European Union is composed of 28 member states with potentially diverging strategies and long-term ambitions. “Nevertheless, this diversity may equally prove to provide rich grounds for a first international cooperation on AI,” says Stix, the author of a new report entitled “What’s Stopping the European Union From Achieving AI Leadership?” which is scheduled to be published in late September. She points to a recent EU Digital Day declaration entitled “Cooperation On AI” as a sign of progress.

“One recommendation I would propose for Europe is to create a single Europe-wide agency for disruptive innovation,” says Stix. This proposal was initiated by JEDI, a group representing the deep tech ecosystem in Europe. Such an agency could pool existing funds across the European Union and divert them towards fewer but higher-risk projects and research which may not receive funding otherwise. That said, in the AI field JEDI

remains cautious, pointing to the market fragmentation created by French, German and European politicians all wanting their “own” AI strategy. JEDI — which is now operational — is setting up a pan-European fund of €1 billion for fundamental research projects similar in nature to The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), an arm of the United States Department of Defense which is credited with helping create a precursor of the Internet known as DarpaNet and other innovations. Its 120-strong members include most presidents of major research institutions, executives at large European technology groups and the founders of deep tech startups. “Europe, starting with France and Germany, needs to focus on disruptive innovation as this is the only way to leapfrog and become technological leaders again,” says André Loesekrug-Pietri, a venture capitalist who was a member of one of French President Emmanuel Macron’s ministerial cabinets in 2017. The EU’s huge research projects, which eat up billions in funding, are launched too slowly, spread into too many directions and are “not at all results and speed oriented,” he says. “Europe has under- estimated how much we are living in an accelerated world where winner takes all,” says Loesekrug-Pietri. “We need fast decision-making, thinking outside the box, high risk/high yield initiatives, bold investments, an independent ability to change/stop, ambitious goals and fast prototyping.” JEDI will be first funded by EU regional governments (France and German regional governments have already signed on) but will be uniquely co- managed by the entrepreneurial tech system to ensure it moves fast to reach ambitious goals. It will finance moonshots: projects that are too long-term or too risky for the private sector in four core areas, including human-centric digital transformation, energy and massive improvements in healthcare, three areas that will be underpinned by AI.

The Road Ahead

At the moment, though, the jury is still out on whether Europe can lead on AI, says Paul Daugherty, Accenture’s chief technology & innovation officer and co-author of “Human+Machine, Reimagining Work In The Age of AI.” “As more businesses become reliant on AI technologies, it is increasingly important for nations to address data accessibility issues as this is a cornerstone to driving new growth and innovation,” says Daugherty. “Europe has focused on protecting data through GDPR which is very important. However, many countries have not yet taken the steps necessary to make data more broadly available in a way that will stimulate new entrepreneurial, AI- enabled businesses. Europe must adopt a ‘platform mindset’ and focus on how it can encourage, stimulate, and support hyperscale platforms that compete with the U.S. (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) and China (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent), or it must partner more effectively with these platforms. Individual countries in Europe simply do not have the scale to do this — which is why a pan-European strategy is an essential, albeit difficult, approach.” The German entrepreneur Chris Boos, a JEDI member and the founder and CEO of Frankfurt-based arago, which uses AI to help businesses automate their IT processes, and one of nine members of a council that advises the German government on technology issues, says he is optimistic that Europe can pull together on an AI strategy, and about its entrepreneurs’ ability to compete. France and Germany are aligned on their AI strategies and can influence other EU countries to come aboard, he says. And his company is working on a global AI platform that aims to serve all industries. Elsewhere in Europe’s private sector there is a movement afoot to use AI and blockchain technologies to safeguard data privacy in ways that could profoundly change the way the Internet and social networks operate and — in the opinion of some — better reflect European values. For example, Fabric Ventures, a London-based venture fund, is dedicated to investing in decentralized data networks that enable individuals to regain data ownership sovereignty, while powering a new level of technological experimentation and becoming the “data substrate” for artificial intelligence. “Nothing is going to happen in a heartbeat,” says the British serial entrepreneur Richard Muirhead, a founding partner of Fabric Ventures. “This is quite a fundamental shift so there will be a period where it is going to feel like hard-going.”

The road ahead will be anything but easy for Europe, says Soulié, another JEDI member. In China the country has a government which is strong, has a vision and the political power to push its agenda, she says. “We don’t have that precise vision about where we want to go and what is it is we want to achieve. Even if the Commission had the vision, who has the power to push it? So what can we do in Europe? It is going to be tough, very tough. We have technically good people, a good system of education, but we do not yet have a common articulated vision of what precisely to do next.”

Europe needs to take both a bottom-up and top-down approach because “you can’t impose a vision at the European level if you can’t ensure that everyone is aligned,” says Soulié. “How these two ways can contribute to success in AI is going to be the challenge for Europe these next few years, if we do not want to be left in the situation where our companies are wiped out by their Chinese and American competitors, selling to us non-ethical products, like what GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon) does today.”