The Tallinn Digital Summit 2025, an invitation-only global leadership forum taking place October 9 and 10 in Estonia, is convening at a critical moment in time.

As artificial intelligence and exponential technologies become increasingly central to national power, economic prosperity, and global resilience, the international community finds itself at a decisive juncture. The summit, which is being hosted by the President of Estonia, says it is convening the gathering because divergent visions for technological development and governance have emerged across the transatlantic alliance and globally, with recent dialogues at the Paris AI Summit, World Economic Forum, and Munich Security Conference revealing competing priorities among key global actors. As the technology races ahead and begins to impact every stage of people’s lives, business leaders and governments are struggling to keep up.

Estonia led the world in digitizing government. It is currently leading the world in introducing GenAI into public schools. The Tallinn Digital Summit will test whether it can act as a catalyst to close the Responsible AI implementation gap and help companies and governments build trustworthy AI.

Less Than 1% Of Organizations Are Fully Implementing Responsible AI

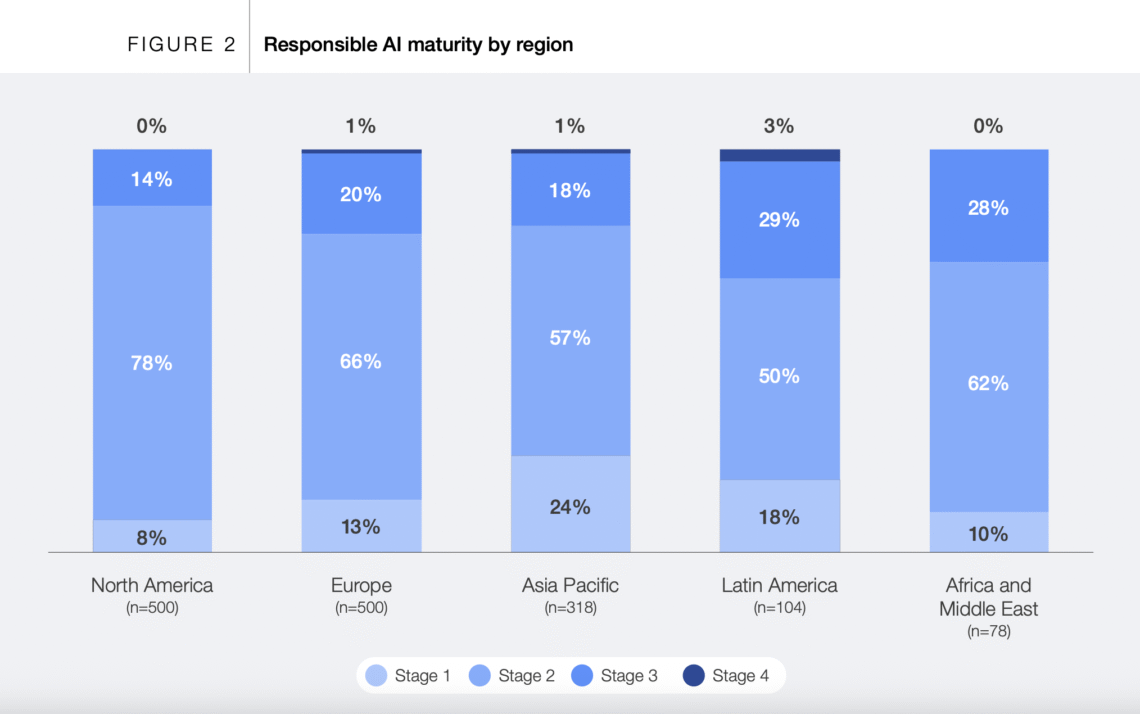

Measured on a four-stage maturity scale, a 2025 survey of 1,500 companies found that 81% remain in the first two early stages of responsible AI, says a September World Economic Forum report. While the number of companies with a stage 3 maturity increased from 14% in 2024 to 19% in 2025, less than 1% of companies are at stage four. This limited maturity is prevalent across organizations, regions and sectors. (See the attached graphic from the Forum’s report. It was sourced from research by Accenture and the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI)

“Without robust governance, risks such as bias, misuse and erosion of public trust grow sharply,” says Cathy Li, Head of the World Economic Forum’s Centre for AI Excellence and a Member of the Forum’s Executive Committee. “This responsible AI implementation gap risks slowing down adoption and ultimately undermining the competitive advantage that AI could provide if implemented responsibly.”

Trouble is “though the ‘why’ of responsible AI is largely understood, the ‘how’ remains elusive to most organizations,”says the Forum report.

The Forum’s playbook is designed to bridge the implementation gap by moving responsible AI from theory into practical actionable steps, says Li, who co-authored the report’s introduction. “The aim is not to prescribe a one-size fits all solution but to give organizations and governments a modular framework that can be adopted to their maturity level, sector and regulatory environment,” she says.

The playbook builds on the work and advances the objectives of the Forum’s AI Governance Alliance which now has over 650 members from industry, government, academia and civil societies.

Getting To Global Consensus

Despite best efforts by the Forum and other international bodies, getting everyone on the same page is proving to be tough.

In 2023, under Japan’s presidency, the G7 launched the Hiroshima AI Process, resulting in the Hiroshima Process International Code of Conduct for Organizations Developing Advanced AI Systems, a voluntary code that promotes ethical, transparent and secure practices. To reinforce accountability, the G7 and OECD introduced a voluntary reporting framework in 2025 for organizations in member and partner countries. While initial reports were submitted, variations in detail and transparency highlighted limitations in consistency and comparability, according to the Forum’s report. The framework’s voluntary nature also raised challenges in participation and adherence. The G7, under its Canadian presidency, is exploring additional incentives and clearer guidance. There is also a Hiroshima forum led by Japan for broader collaboration through the AI Process Friends Group, which now comprises 56 countries and regions. Increasing participation by organizations across diverse jurisdictions will also require reporting requirements to consider language and timing, the report says.

What Governments and Companies Can Do Now

The real-world case studies – from companies such as Telefonica, Infosys and e& (formerly Etisalat Group)and governments such as Dubai and Saudi Arabia – outlined in the Forum’s report are a good starting point for the discussions in Tallinn. The report offers practical examples that show companies and governments what they can do now to ensure that they are implementing AI responsibly even though a global approach that everyone can agree on is still a work in progress.

The Forum report concludes by saying that governments will need to continue to encourage a context in which industry, academia, civil society and the public contribute to a holistic, trustworthy AI ecosystem.

The Tallinn Digital Summit will try to do just that. Elsa Pilichowski, Director, Public Governance, OECD, is scheduled speak about governing with AI. Laura Gilbert, PhD, Senior Director of AI and Head of the AI for Government program at the Tony Blair Institute, will speak about the UK’s AI wins and lessons learned. Kristina Kallas, PhD, the Estonian Minister of Education is expected to outline how Estonia is upskilling its population through its AI Leap program, a public-private partnership which is introducing GenAI tools in all public secondary schools in the country. The summit will also give a voice to proponents of trustworthy public AI.

Ensuring AI Serves the Public Interest

Upskilling people in how to use and develop AI tools is not enough. To close the responsible AI gap and build trustworthy AI “we must train engineers, computer scientists, and data experts in ethics, law, and policy,” says summit speaker Carolina A. Rossini, Director for Programs, Public Interest Technology Initiative and Professor of Practice, School of Public Policy, at the University Of Massachusetts. “A public interest technology approach is ideal, because it brings together disciplines that rarely speak to each other yet are all essential to shaping the future workforce.”

Beyond the people that are hired and trained to run AI systems “we must think about responsibility across the entire AI lifecycle: from early design choices to the companies and technologies we invest in,” says Rossini, who is scheduled to speak on a panel entitled Power To The People: Human Centric Data Governance in the Age of AI panel, which will be moderated by The Innovator’s Editor-in-Chief.

A public interest technology approach will be essential in addressing the current imbalance of power, says fellow panelist Liv Marte Nordhaug, CEO of the Digital Public Goods Alliance (DPGA) Secretariat, a speaker at the Tallinn summit. U.S. and Chinese AI companies dominate the market for AI chips and large language models.

A key takeaway from the AI Action Summit in Paris was the emergence of a new AI bloc comprised of Europe and much of the rest of the world, built around open source. Some 58 of the countries attending the summit – which together represent one half of the global population – signed a statement committing to promoting AI accessibility to reduce digital divides; ensuring AI is open, inclusive, transparent, ethical, safe, security and trustworthy; avoiding market concentration; and making AI sustainable for people and planet.

It will take coordination, commitment and financial investment to make that happen and there is no time lose. Countries that don’t want to be left behind will adopt what is commercially available. The choice to use OpenAI and Google to introduce chatbots into Estonia’s public schools, is an example. The decision was made because there were no other options, Riin Saadjarv, an advisor to Estonia’s Ministry of Education and Research, said in an interview with The Innovator.

The Power to the People panel will focus on how to move things forward. “We need to regaining sovereignty over technology even if we can’t control the whole supply chain,” says scheduled panelist Dan Bognanov, PhD, Chief Scientific Officer at Cybernetica, an Estonian company that specializes in technologies to enable secure digital societies. “We solve the problem with software that is designed to distribute or retain control. This has made our approach interesting for smaller nations, but now also increasingly larger ones.”

Cybernetica were the security architects of the Estonian X-Road service interoperability platform. In 2001, its current CTO argued that a decentralized system where each agency has its own data, is better for security: . Today, Estonia, Ukraine and several other countries run this architecture. Cybernetica’s UXP, which it sells to other governments, is an advanced version of this platform.

The Smart-ID digital signature and authentication system, operated by SK ID Solutions, is based on Cybernetica’s SplitKey research and patent. It distributes the private key (the trust anchor for digital identity) between the service provider and a user’s phone. This Smart-ID system has 3,6 million users).

Today, Cybernetica is building a decentralized cross-border statistics platform for EUROSTAT, the European Statistics Office. “We believe that the need for digital sovereignty will, once again, require people who know how to run their own systems,” says Bogdanov. The platform is based on Cybernetica’s 18 years of research into secure multi-party computation technology and the Sharemind MPC platform. It is designed to allow EU countries to share data securely, without losing control over their processing.“

The Digital Public Goods Alliance is taking another approach to overcoming barriers to a more open and equitable way of building AI systems that serve the public interest.

Besides stewarding the Digital Public Goods Standard (a set of specifications and guidelines designed to maximize consensus about whether a digital solution conforms to the definition of a digital public good) and maintaining the DPG registry, the DPGA Secretariat has also been involved in shaping policy recommendations for the G7 and G20 on the democratic governance of AI and datasets and democratizing AI for the public good (i.e. with Digital Futures Lab), and recently co-authored a whitepaper on public AI. And, it is currently mobilizing DPGA members and others to find ways to develop and unlock more high quality open training data that can advance public interest AI.

The term “open-source AI” is often misused to describe systems that only have open weights but where there is no transparency and sharing of the data the system has been trained on. This lack of transparency poses a significant risk, as these systems are increasingly shaping the public’s norms, values, understanding of reality, and access to information and services at the most fundamental level, Nordhaug says. The development of public interest AI, including AI systems as digital public goods, depends on the opportunity to train models on both existing and new high-quality openly licensed datasets, she says. Many challenges exist that impede doing this at a larger scale, one of which is the resources required to produce and share open data in different geographical contexts.

One way to address this challenge is by creating an adaptable and reusable toolkit that can be recommended to countries and stakeholders to facilitate the collection, extraction, processing, and preparation of data. The DPGA is calling for digital public goods that can make identifying, preparing, sharing, and using higher-quality open training data easier, particularly for use cases such as the development of language models that address language gaps in AI development, solutions for public service delivery and research-based climate action (monitoring, mitigation, adaptation).

“We need to think of AI capabilities as part of our infrastructure, and ensure their main mandate is to serve the public interest,” says Nordhaug. “One of our most urgent tasks right now is to save the public discourse from AI-boosted manipulation and strengthen genuine democratic participation through alternative social media platforms. Because the more polarized and fragmented we become as societies, the less able we will be to make the kind of bold, broadly anchored, complex decisions that public interest AI require,” she says. “It quickly becomes a Catch-22, because we need a strong enough public discourse to save the public discourse. The time window for acting is therefore now!”