The Innovator surveyed 20 influential figures to assess how France is doing in its efforts to nurture a vibrant tech sector.

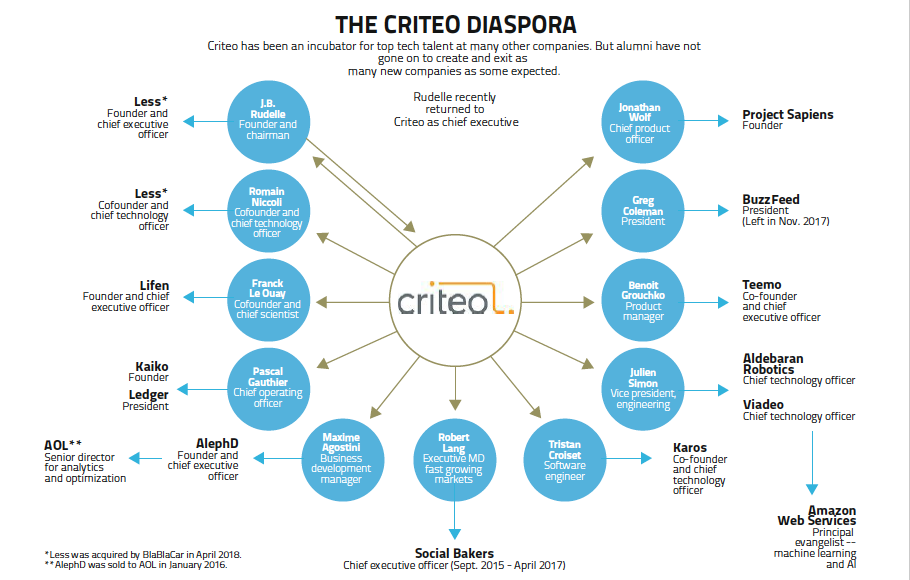

The online advertising firm Criteo is the poster child of France’s newfound success in technology. Founded in 2005, it was nurtured by French founders, expanded early to the United States, and went public in a spectacularly successful listing in New York in October 2013 with a $2 billion valuation. Criteo executives, such as its founder J.B. Rudelle and former chief operating officer Pascal Gauthier, moved on to help found a new crop of French startups.

This feel-good story has lately gone sour. Criteo shares have halved in value in the past year to trade below the IPO price. The business model of re-targeting ads to people as they surf the web is under assault as tracking gets harder, and critics say Criteo has done a poor job of diversifying into new products. In late April, Rudelle was called back by the Criteo board to retake the helm as chief executive and fix the mess.

Criteo’s current woes are not the only issue. Gauthier wonders why his former colleagues at Criteo haven’t founded more new companies or had more big exits by now. Such renewal has been typical in the tech world since alumni of PayPal, an early Silicon Valley success story, went on to fund many emblematic startups like Palantir, Tesla Motors and LinkedIn.

“Creating unicorns is still not a French speciality,” says Gauthier, while looking out over the Paris skyline during an interview at the top of the Pompidou Museum.

France is home to only three unicorns, or private tech companies worth more than a billion euros, while the United Kingdom has 10, Germany 5, Switzerland 3, and Sweden 2, according to a March Dealroom.co report.

Gauthier is trying to add another unicorn to the list: he is now at the helm of a Paris-based start-up called Ledger, which builds infrastructure for blockchain and cryptocurrencies by leveraging France’s traditional strengths in encryption and chip and pin technologies.

Other aspiring French unicorns are also in the pipeline. But the Criteo saga stands as an example of how tough it can be for companies to stay on top of the fast-changing technology market. It also shows how much remains to be done to realize the dream of making France a true technology leader. While access to capital has improved and more people are flocking to entrepreneurship, too few companies manage to reach critical mass. Too many are still selling out early, often to foreign buyers.

Nicolas Dufourcq, who heads the state-backed bank BPIfrance, which is a major tech investor, says he often urges entrepreneurs not to sell their companies, and instead emulate an earlier generation of French companies. “I tell them to persevere, keep going. The founders of Atos, Capgemini, Dassault Systemes could’ve sold out many times but didn’t.”

So why aren’t more heeding Dufourcq’s advice?

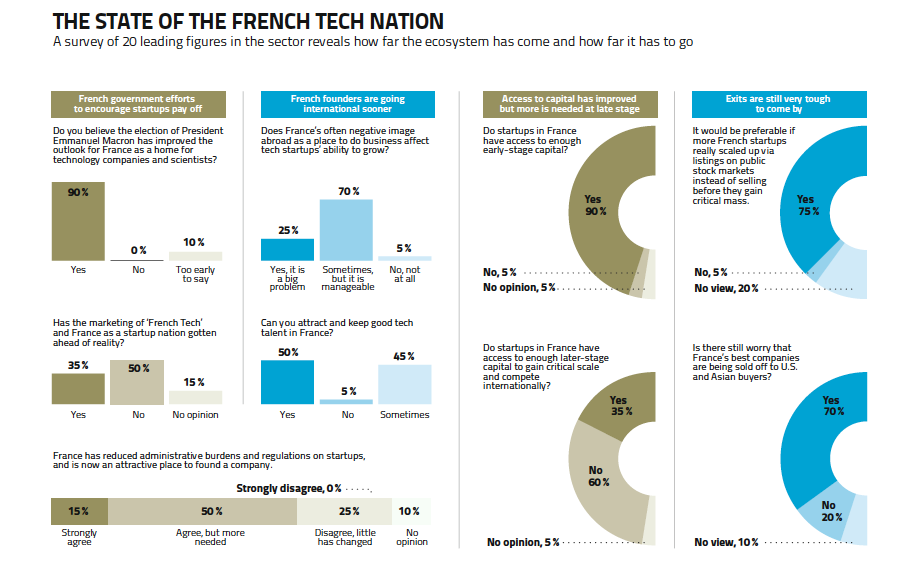

To assess the progress of the French ecosystem, The Innovator surveyed 20 influential figures working in the field today, including the BPI’s Dufourcq; the former French minister Fleur Pellerin; the founders of the promising start-ups Algolia, ManoMano and BlaBlaCar; and venture capitalists from Index Ventures, Partech Partners, Balderton Capital, ISAI and Ring Capital. (The complete list of the respondents who agreed to be named is on pages 24–25.)

Our aim was to get a sense of what has been achieved in the past decade and what remains to be done. We asked questions on the following areas: France’s efforts to promote startups, access to capital, regulation, administrative burdens and tax, access to talent, prospects for exits, and the educational system. We also conducted interviews with many of the participants.

Here are our findings:

LESSON #1 — French government efforts to encourage start-ups are paying off

Last June, President Emmanuel Macron spoke to a raucous crowd at the opening of Station F, the massive start-up incubator funded by the telecoms billionaire Xavier Niel. “I want France to be a startup nation, a nation that works with and for the startups, but also a nation that thinks and moves like a startup,” Macron said. Since then Macron and his ministers have never missed an opportunity to talk up French Tech or visit Station F.

It’s easy to be cynical about such hype. In fact, French government efforts to make life easier for startups began almost a decade ago and was backed by the two prior presidents, not just Macron. The most visible of them was the creation of the French Tech label by then-junior minister Fleur Pellerin. Tech start-ups widely adopted the image of the red rooster and it helped raise awareness both domestically and abroad at big tech fairs like CES in Las Vegas.

Beyond the French Tech label, additional important changes were made. Pro-business reforms were enacted, such as ending penalties for founders whose companies declare bankruptcy. Most important, the BPI was given a broader mandate and a bigger budget to fund innovation. The state-backed bank has invested €1.3 billion annually for the past three years, a big jump from its traditional levels. As a result, the BPI has become the biggest single backer of French venture funds, and also made direct investments in start-ups such as Sigfox, Devialet, and Doctolib.

Macron has gone further on the reform front to make hiring and firing easier for all types of companies. He also introduced a flat tax rate of 30% on capital gains and dividends, which Xavier Niel has said is one of the most significant reforms for companies looking to invest in new technology.

Our survey respondents unanimously say France’s efforts in recent years went beyond mere marketing and have really helped tech entrepreneurs. And 90% of them also think that Macron’s election has helped the outlook for France as a home for tech companies and scientists.

To build upon this success, several of those surveyed say more must be done to simplify corporate law so as to make it more flexible and lower the costs involved in founding companies. Nicolas Colin, one of the founders of the incubator The Family who has also worked in government, says regulations still too often favor old-school incumbents over disruptive startups. “In every sector, the government should adopt policies to encourage innovation without letting corporate lobbyists wreck the process,” he says, citing healthcare, education and agriculture as areas to focus on.

LESSON #2 — French founders are going international sooner

For too long, France has been a trap for startup founders who first focused on building a business domestically, and neglected or delayed developing sales abroad. Several of the respondents to our survey cited this “France first” approach as one of the historical reasons why the country hasn’t produced more large tech companies in the past decade.

“Unlike the U.S. or China, France simply isn’t big enough for unicorns to subsist only on local sales,” says Nicolas Celier, a venture capitalist who co-founded a new fund called Ring Capital last year. “Start-ups here need to think about expanding internationally much earlier.”

Thankfully, this provincialism is changing. The long-distance carpooling service BlaBlacar, one of France’s unicorns, went on an aggressive international expansion in 2014 and 2015. Armed with roughly $300 million in VC funding, it launched in India, Brazil, Russia and central Europe, buying four companies along the way. Some markets didn’t take off but Russia is now BlaBlaCar’s biggest market in terms of rides.

Algolia, a fast-growing French enterprise software company founded in 2012, is another good example of how France’s new breed thinks globally. Its founders aimed to build a global business from day one so they made English the official language for the staff and the website. After going through the prestigious Y Combinator accelerator in Silicon Valley, Algolia opened its headquarters in San Francisco. But 60% of its roughly 200 employees and all its engineering talent remains in France; the two co-founders split their time between the U.S. and France.

Algolia creates technology that allows developers to build a search engine for their app or website. It has reached roughly $20 million in annual recurring revenue from subscriptions, two-thirds of which are in U.S. “The distance and time difference can be a pain,” says Nicolas Dessaigne, one of the co-founders. “But we knew we could build a great team of engineers in Paris much faster than in the Valley, where our brand is not well known.”

This hybrid approach was also used by Criteo, which expanded into the U.S. early on but kept its software development teams in Paris.

Martin Mignot, a partner at Index Ventures, which has backed Algolia and BlaBlaCar, sees the dual-country strategy as a competitive advantage. “I do think French engineers are really high quality — better and cheaper and more loyal then their U.S. counterparts,” says Mignot. “But the French are pretty terrible at marketing so it is good to bring U.S.-style marketing and sales talent and merge them with French engineers. That is the most powerful combination.”

Several of those surveyed agreed that France simply doesn’t have enough experienced tech executives who can drive growth into the hundreds of millions of euros. “Hiring executives that have worked at large tech organizations is expensive in the U.S. but at least you can find them there,” says Nicolas Brusson, a co-founder of BlaBlaCar. “You still struggle to find them in Europe, especially in Paris.”

LESSON #3 — Access to capital has improved but more is needed at later stages

The good news: France is no longer a laggard in the European venture-capital stakes. Total investment into French start-ups hit €2.5 billion last year, a three-fold increase from 2013 levels, according to Dealroom.co data. This remains much smaller than the €7 billion euro invested in the U.K. last year, but the fact that France is on par with Germany is significant progress.

Our survey respondents believe that France has ample funding for early-stage start-ups. About 90% say access to early funding has improved in the past five years, and 70% think it is now adequate.

But behind the rosy numbers of rising tech investment, it can still be very difficult for entrepreneurs to raise money, especially in the business-to-consumer segment. Philippe de Chanville, one of the founders of ManoMano, an online store for do-it-yourself tools and gardening supplies, got rejected by some 30 French funds along the way. The low point came when a prominent French angel investor refused to believe the company’s rosy revenue targets. He snapped at de Chanville and his co-founder Christian Raisson that he “didn’t invest in clowns” before stomping out of the room.

Eventually ManoMano did secure funding from Partech Partners and the BPI, among others. Since then, the business has grown rapidly, expanding to serve Spain, Italy, Germany and the U.K. It’s now widely considered a future unicorn and is expected to make €500 million in sales this year.

“Don’t listen to what local investors tell you because they will kill your dreams,” says de Chanville. “It’s a problem with the general mindset. “There is a real lack of ambition and believing that success is possible.”

The picture is darker when it comes to late-stage capital, which promising startups need if they are to truly be able to scale up. Some 60% of those polled say there is not enough growth capital available nowadays in France.

To be fair, growth capital is lacking in Europe in general, so this is not a France-specific problem. As a result, the best French startups often turn to well-known U.S.-based investors for growth capital. The thinking is that U.S. funds also bring with them expertise and know-how about international markets that most French VCs cannot match.

That’s what ManoMano ended up doing. In September, the company raised €60 million in a round led by General Atlantic, a U.S.-based growth fund.

LESSON #4 — Exits are still very tough to come by

The goal of all startups is to achieve an initial public offering or exit by selling to a larger company. It’s only when an IPO or exit occurs that the venture capital investors who backed the startup are rewarded, ensuring a healthy ecosystem.

A large majority of our respondents expressed the desire that French startups stay independent longer so as to get big and list shares in Europe. But this route remains difficult: European equity investors are less knowledgeable about technology than their U.S. or Asian counterparts. Liquidity for listed tech shares can be lacking.

As a result, listing locally is less attractive and riskier, says Greg Revenu, a managing partner at investment bank Bryan Garnier. “Companies going public on Euronext have traditionally seen lower growth than ones that go public on the Nasdaq,” he says.

Ideally, Europe should create an equivalent of the tech-focused Nasdaq stock exchange, said Sebastian Soriano, who heads ARCEP, France’s telecoms regulator. Over time, European investors would become more tech savvy and more startups could list regionally.

Dessaigne, the Algolia CEO, admitted that his firm would likely choose New York if it were to do an IPO. “It would be too hard to do it in France today,” he says. “We can’t make that decision out of ego or national pride — it has to be what’s best for the company.”

Since listings in Europe remain difficult, many startups choose to sell to corporate buyers. A large majority of our respondents expressed the desire that French startups stay independent longer so as to scale up and list shares in Europe.

About 70% of respondents said they worry that the best startups are still being sold to foreign companies. They often don’t have much choice, since large French companies aren’t in the habit of buying startups. There are signs that things are evolving: BNP Paris and the telecoms group Altice bought startups last year. But these were relatively small deals worth a few hundred million euros.

Selling to corporates can also go terribly wrong — just look at how Nokia botched its 2016 takeover of the French health-device maker Withings. The founders recently bought back the company from Nokia to try to revive it.

Phillippe Dewost, a seasoned tech executive who now heads Leonard, VINCI Group’s new open innovation program, cautions that successful exits will be the true measure of France’s progress in tech. The former government adviser also worries that the torrent of public money deployed by the BPI in recent years may not generate spectacular returns.

“Lately we’ve all been cheering at any new investment round and proclaiming our unicorns,” Dewost said. “But we shouldn’t forget that valuation is opinion; cash out is a fact. La French Tech will only have delivered once exits occur and funds are returned to all limited partners, including the French government.”

Philippe Collombel, co-managing partner at Partech Partners, urges patience. “Let’s wait to see how companies like Sigfox and Algolia do,” he says. “It is still too early to declare victory or defeat. The story is still in the making.”

Jennifer Schenker contributed reporting to this story.