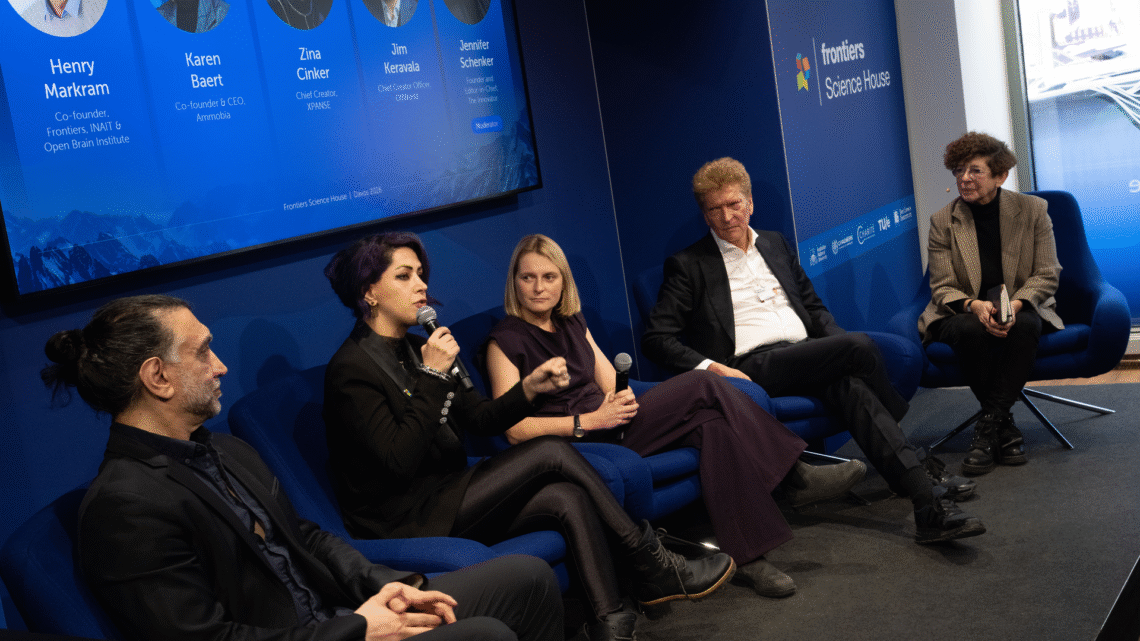

This year’s annual meeting of the World Economic Forum marked the launch of an accredited side event called Frontiers Science House, organized by Frontiers, the open science publisher. Frontiers Science House hosted more than 50 sessions on the latest breakthroughs in science and technology between January 19 and 23. The week-long event wrapped up with a panel on the 2035 Science Roadmap, moderated by Jennifer Schenker, The Innovator’s Editor-in-Chief. (The Innovator was a media partner of Science House).

The 2035 Science Roadmap panelists included neuroscientist Dr. Henry Markram, a co-founder of Frontiers and Science House. He’s a professor of neuroscience at EPFL and is also a co-founder of INAIT, a Swiss startup that recently emerged from stealth mode. It has been working, since 2018, on deciphering the neural code, developing a digital brain operating system, and pioneering causal learning to empower digital brains to accumulate cognitive skills. Now, after surpassing technology and product benchmarks and forging strategic partnerships, INAIT is launching inait Adaptive Machines (iAM) across industry verticals, starting with fintech and robotics. Panelist Karen Baert, a World Economic Forum Technology Pioneer, is Co-founder and CEO of Ammobia, a developer of breakthrough low-cost ammonia production technology used in green nitrogen fixation. In January it announced a $7.5 million seed round to scale its technology, which uses advanced materials science and reaction engineering to considerably reduce ammonia production plant capital expenditures. With the new capital, the team will build a pilot facility to derisk its reactor technology and select a customer cohort for commercial demonstrations. Investors include Shell Ventures, ALIAD (Air Liquide), MOL Switch (Mitsui OSK Lines), Chevron Technology Ventures, and Chiyoda Corporation. Green nitrogen fixation is one of the top 10 emerging planetary health technologies that was identified in a report that Frontiers prepared with the World Economic Forum last year. Panelist Dr. Zina Zahari Cinker, a condensed matter physicist, exponential technology strategist and deep science advocate. She serves as the Director General of Matter Group, an international deep science thinktank of 30 country chapters and 20,000 members. Under her leadership, Matter Group has become the catalyst behind two exponential tech forums, Puzzle X in Barcelona and Xpanse in Abu Dhabi. Hosted by ADQ – the Abu Dhabi-based investment and holding company – XPANSE 2024 convened 3,000 of the world’s brightest minds, Nobel Laureates, industry decision-makers, scientists, presidents of universities & policymakers from 89 countries to set the horizons of AI & AGI, quantum, brain-machine interfaces, next-gen materials, genomics and more. Panelist Jim Keravala, is CEO of OffWorld, a Pasadena, California-based startup which aims to enable human settlement of space by developing a new generation of AI-powered industrial robots. (Click here to read The Innovator’s separate story about Keravala’s company OffWorld.)

Below is an edited version of their on-stage conversation, which was capped off by closing remarks from neuroscientist Kamila Markram, a co-founder of Frontiers and Science House.

Q: Jim let’s talk about what will happen here on Earth and where you see things going in space.

Jim Keravala: We are really entering the greatest moment in scientific history. The leaps that will emerge out of that will give us the new materials, control systems, dynamics and production methodologies, not only on Earth but in space, to literally build anything that we can imagine within 10 years. The key is going to be manufacturing materials extracted and obtained and fabricated outside of Earth’s gravity. I think this next 10 years is the biggest inflection point in human history and the opening of a frontier greater than that which we’ve seen in centuries past.

Q: Can you talk a little bit more about the role of robots, both on Earth and in space? During the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos Elon Musk told participants that soon we are going to have more robots than people on Earth. Is that a good thing?

Jim Keravala: From a consumer perspective the range of robotics and automation systems that we’ll see over the next five years, I think will have a slower uptake, not necessarily because of the technology curves, but because of our cultural and operational ability just to absorb and integrate them into our daily lives. There is lots of unpaid labor and unpaid work, whether it’s driving kids to school or looking after families. Robots may well take on those roles. The challenge is how do you economically engage robots into a domestic operational environment? What we’re doing now is building swarms of rugged industrial robots to do underground mining construction and infrastructure repair, and we’ll start to use those to build civilization out into the solar system before the 2040s. I think we still got a 10-year curve, at least, to get the performance, productivity, the materials, ruggedness and robustness and the longevity of these systems, so that they can operate for a decade without human maintenance. We will see a quadrillion dollar economy by the 2060s, most of it underpinned by autonomy and robotics and new materials and science. The question for us as humanoids is how do we leverage that? I think our productivity is going to go up, our imaginations are going to be unleashed, and what it will lead to, ironically, is a trust economy. We will trust human to human interaction, as we can’t trust whatever is digital, whatever is automated, not from an operational perspective, but just from a humanistic perspective.

Q: I’m going to turn to you now Henry, because for robots to really be useful in in the home and in space they need to understand the physical world. How does your work help advance that understanding?

Henry Markram: Today we have this incredible first wave of AI. What I think is that in one year, maybe two, we will finally realize that the current paradigm that is being used to get to AGI [Artificial General Intelligence], is not going to get us there because it’s based on the past human record. The way to think about today’s AI is that it captures knowledge, but it doesn’t understand it. Today’s AI is an observer. It is not participating in the world. This is not possible through correlation. It’s only possible if you do what animals are doing and what we’re all doing, to be born in the world and to grow up in the world, learning cause and effect. To make AI a part of the world you need to build a machine that becomes part of the world. That’s what INAIT set out to do. We’ve solved how to learn causality, which gives AI understanding and participation in the world. We know how to do that now so I think within two years, the robots are going to be sitting next to us, and they will be powered by participant AI. These are the kind of robots that are going to be able to do space exploration or mining or agriculture, or take over some of the dangerous work, and do explorations which are very difficult for humans. I don’t think one should immediately go to home companions. There are far more urgent use cases for the planet and for economic development. But I do see the timeline being accelerated. I think it’s here because we’ve developed the technology now to leverage the actual brain to do this. And so, by 2035, I think there is going to be a complete transformation. We’re going to have participant robots. They’re going to be part of society. There will be many. Elon may be right that there’s going to be more robots, maybe not humanoid robots, but there’s going to be all kinds of different robots that are going to be part of society, and we can think of them as a digital species. I think that it’s going to be an exciting future. There’s going to be so many new opportunities, so much stimulus to economic development and innovation.

Q: Karen one of the big challenges we’re facing right now is climate change, and we need science to solve it. You’re working on clean ammonia. How is this going to help the planet and change everything from agriculture to shipping to industry?

Karen Baert: It’s great to be here, and what a powerful way to end this inspiring week amongst fellow technologists and scientists and innovators. Before answering your question, I want to take a step back and reflect on the week here and all the inspiring and thought-provoking conversations. My world, the energy world, the sustainability world, is very divided, but what gives me a lot of hope is that when we think about how we provide more affordable energy in a sustainable way for all, the one thing that everyone here in Davos and more broadly agrees on is that technology, science and innovation will get us there. That’s what makes me hopeful now about green nitrogen fixation. What is it and what does it mean for the world, and what can it mean for the future? Nitrogen fixation is essentially the concept that we take nitrogen, one of the most abundant elements on Earth, and we combine it with other elements to produce something useful. Before that technology existed, we were using, essentially guano from South America, natural components to fertilize our lands. Since 1914 since Haber and Bosch invented the Haber Bosch process, synthetic ammonia production started, and that really enabled us to double population growth rapidly. More than half of the world’s food depends on ammonia as a fertilizer. That was the first revolution in ammonia, but today we’re going through a second revolution. Today ammonia is, of course, crucial for food security, but it is becoming even more important, because now ammonia is also an energy carrier and a maritime shipping fuel. So soon enoug, the ammonia market will grow from $100 billion market today to a $500 billion market and will sit at the critical intersection of not just food security, but also energy security sustainability. Why? There are two new use cases for ammonia going forward. Ammonia will be used as a maritime shipping fuel, which will decarbonize 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. On top of that, ammonia will be used as an energy carrier, a way to redistribute renewable energy across the world. Today all the ammonia is produced from natural gas. There’s a lot of amazing technology innovations happening, including our approach at Ammobia, where we’re figuring out how we can produce ammonia in a more sustainable way, from thermochemical pathways, electrochemical pathways, plasma pathways. That’s really going to change the world and change the energy and fertilizer landscape. It will enable us to produce ammonia from renewable energy, from bio-based sources. We will be able to produce ammonia more locally, making us more independent from fossil fuels, and bring a lot of power, literally and figure figuratively, to emerging markets, because we will produce ammonia from renewable sources, and then bring that ammonia to areas that need energy inputs, such as Europe and Asia. So, a lot happening in this space.

Q: We’ve heard how technology is going to help us explore new worlds and feed and power this one. Zina, you are looking at exponential technologies across the board. What is your vision for 2035?

Zina Cinker: What excites me the most about what is coming is the story of matter. I’m a material scientist by background so I’ll talk about atoms and molecules. If you look around us, everything, almost everything, that we touch and we feel is made of these building blocks, these Lego pieces. And sometimes I do this exercise of thinking, if we close our eyes, and everything just crumbled right now, into its most elemental pieces, if we opened our eyes, there will be less than 100 Lego pieces on the floor. The beauty and magnificence of this life, from this squishy thing inside our skull that is thinking, perceiving, to our super computers, to the food we eat, to these buildings, is that they’re all made of the same 100 Lego pieces. As humanity has learned how to put these pieces together, we have created different facets of civilization. The history of humankind is marked by mastery over matter, from the Bronze Age to the Stone Age to the Silicon Age. I am often asked, what is the next phase? What is the next material? If I give my opinion, I believe that the next age will be the age of mastery over matter. I believe that we are the pivotal point in the history of humankind, the point where we have four major areas of technology that have reached, at the same time, the point of maturity. This includes genomics, multiomics (an approach in the biological sciences that integrates data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other omics technologies to provide a comprehensive understanding of biological systems), our ability to build things from the atomic scale to quantum technologies as well as AI and our mastery over zeros and ones. These four areas are reaching a point of maturity, and their progression is no longer linear. They’re exponentially increasing their speed, but also the speed of each other. I believe that it will give us the foundation of becoming masters of over matter, if we have the capacity of putting atoms and molecules together with nano assembly, if we know how, when we put this atom and this atom together, what is going to happen without me having to go to a lab and get a PhD, then we can become masters of matter. We can predict what we can build and we can build it. That’s where I see us going towards and that will impact so much in the energy sector, in the pharmaceutical sector, in the longevity sector.

Q: The four of you have painted a vision of where science and technology could take us by 2035. What could hold us back?

Karen Baert. In my mind, there’s three things that really need to change. The first one is we need to work together with industry. I’m a huge believer in technology and I also really believe that we innovators, scientists, cannot do it in a vacuum. We need to work together with large corporations to accelerate our innovations and bring them into the market as fast as possible. This week we heard multiple CEOs of massive companies say that they want to increase their budget for R& D and innovation. This is instrumental for us to advance our technologies fast enough, because we don’t have time to lose. The second one is we need regulations. But more importantly, we need consistent regulations so that we can make sure that our research is aligned with these priorities. The third thing is that within the academic world, within the R& D world, within the innovation world, we need to work together across countries, across boundaries. Our company Ammobia would not have existed if it wasn’t for the openness of all the academics that had worked in nitrogen fixation and ammonia over the last decades. We spoke to all of them, and putting the knowledge of all of them together is what enabled us to come up with what we think is a disruptive innovation in ammonia production. If we don’t talk to each other, we lose out on the opportunity to significantly accelerate technology innovation. I think I’ll end on the note that I really think it’s extremely important that we never let our ego stand in the way of purpose.

Q: Jim: In your view what is the best way to build the bridge to the future?

Jim Keravala: Zina you made extraordinary points about our accessibility to new capabilities. That blows my mind. I’m sure all of us, month by month, are gob smacked with what’s emerging. The concentration of wealth and productivity coming from these capabilities is increasing. That represents increasing risk for a balanced global economy. Widening accessibility and opportunity for more people across the developed world, the Global South, is crucial. How do we provide 8 billion people with a consistent level of information about these capabilities? How do we provide accessibility? Because I don’t believe it’s a barrier to entry. It’s a barrier to information. It’s a barrier to inspiration, and there’s a barrier to motivation. You know, 1% of people might see that all these capabilities are there, and then 1% of those might do something about it, and 1% of those will persist when the first time it doesn’t go right. How do we increase those numbers? Because what’s coming over the next one, five and ten years is a huge revolution in even the very nature of science as we as move to utilizing semiconductor manufacturing tooling to actually producing beyond MEMS and Femto level machines that can create new materials, new bones, Bose Einstein condensate opportunities [ a state of matter in which separate atoms or subatomic particles, cooled to near absolute zero coalesce into a single quantum mechanical entity), integration of quantum gravity into new potential science, and then make that accessible for everyone by 2035? I’m speculating a little bit here, but the barrier to imagination is all that’s in the way now. And so, I think it’s an information effort that we all need to make. Between now and this next Davos, what Frontiers should do is increase the communication and create a toolkit that consists of what we might think of the most obvious information sets about what can be done today. Distribute that to 100 plus countries and make sure the young girls and boys and men and women in schools and across universities are seeing these toolkits that talk about what’s possible now. That’s, I think, the biggest leap we could make in the next 12 months.

Q: Zina, Jim talked about inspiring young people and informing them about what’s possible, but for this to really trickle down all the way down into public schools everywhere, you need the support of regulators. And yet, we are at a point in time where trust in science, knowledge of science at the government level, is in some places at an all-time low. So how do we fix that?

Zina Cinker: I have strong feelings about this. I look at the frontiers of science, and a lot of people ask me when we talk, whether advances like xenobots, brain interfaces, robots, or AI controlling the grid scare me. I tell them no. If there is one thing that scares the bleep out of me and I’m seeing more and more of it in the U.S., is the distance that is being created between science and society. Prior to Covid, I remember reading about these groups of Flat Earthers. We were laughing at it, and we were saying it was a small group of people. Have you looked at how many Flat Earthers there are now? Science Daily published an article that said 2% of Americans believe the earth is flat.

Jim Keravala: But to be fair they do say on their website that they’re the largest Flat Earth Society around the world.

Zina Cinker: They need to change their language apparently. But seriously we need to look at why people are pushing back. This distance between science and society is a symptom. And I think that is a symptom of us having created the ivory tower of science. We create this distance and say ‘Science is correct and believe us when we say this thing, do not question it.’ Science is always developing and evolving. If we tell society, ‘This is science, believe it, it will never, ever change’ the next time that it changes, people will say, ‘You were wrong. Why should I believe in this? ‘And I think that is something that we need to bring to the attention of society. Science is not fixed. We need to highlight the beauty and magnificence of science, like we have done at XPanse.

Q: Henry, can you share your thoughts on this?

Henry Markram: If you look at a book written by Yuval Noah Harari that became so popular, and why this book was so amazing, it was really because of one thing. He showed that the survival of any culture or group of people, was because they could cooperate. What made them cooperate was a common story, a myth, a belief system. I think that if there’s one thing that we want to do to preserve the security of humanity going forward, is to realize that although we’re very different, with different nations, religions, cultures and ethnic groups, we have one common story, which is something we can hang on to, and that is science. Science, this common story that we all have, is the foundation. But you do have this problem, which Zina pointed out so beautifully, is that science has become this ivory tower and there are signs that society is losing trust in it. This is why we started Frontiers, nearly 20 years ago, to open science, because we really believe that you’re not going to convince people that science is right. You know, science is very messy. It’s extremely messy, and it’s supposed to be. That’s part of the process. Once there’s a discovery, there are debates, there are counter science arguments and papers and eventually it self-curates. But that takes years. If you take CFCs, which damage the ozone, it took nearly eight years from the first publication for the debate, the scientific debate, to get to a universal consensus. And that led to the Montreal Protocol. And then there was a global decision. It was one of the few times that the whole world, every single nation in the world, came together and said, ‘Okay, we ban CFCs.’ But in the run-up period, the science was messy. Scientists need to understand that they have to be very careful during this messy period and not say ‘Oh, I’m right. You know, I published this.’ It’s got to go through a self-curation process until it reaches maturation. That is why open science is so critical. It is the only way you’re going to get trust in science. You can’t rely on anything else. You need to let the public participate in the scientific process. Let them understand the messiness of it, let them appreciate the innovation and the potential of it. Let them encourage it and support it.

Open science accelerates innovation. If I find a new method and publish something, somebody can immediately use that new method. You can go to every single university in the world today and you will see that they have a major program on what they call interdisciplinary science. It is not needed. The simplest way to get multidisciplinary science is to open the science. That’s how you break all the silos. Suddenly you can combine physics and astrophysics with chemistry and biology and with philosophy and with social science. It happens instantly. Zina beautifully pointed out that if you collapse the whole world into dust, we have 100 Lego blocks. Innovation is about combination. The only thing holding back accelerated or exponential innovation is to combine technologies from different disciplines. If we want a safe, secure world with accelerated innovation in a way that is equitable and trusted, there is nothing simpler, cheaper and more effective than open science.

Q: Kamila the floor is yours for the closing address

Kamila Markram: “Why did we start Frontiers Science House? We’ve been going to Davos for over 15 years. Henry used to be invited to talk about digital brains, how to reconstruct brains, and then there was a couple of years where we didn’t come. And then last year, thanks to the collaboration between Frontiers and the World Economic Forum on reports, we become a center partner and started coming again. We noticed that scientists were less prominent than they used to be. So, we thought, we have a huge network of scientists, some of the very best scientists in the world, serving on the editorial boards across all type of disciplines, let’s bring them to Davos. And why is that important? Because science, is really the underlying factor on which any type of innovation is built, whether it is these amazing robots that we’re going to soon have in our future, or the artificial intelligence we are building today, which includes an energy layer, the chips, the compute layer, the models layer, and then the applications. Every single layer of this has fundamental science in it. So, we had two objectives with Science House: bring the scientists back to Davos in big numbers and put them smack into the middle of the decision-making table with the policy makers, with the leaders in business, and provide them with a voice. The world turns to scientists for solutions, whether it’s Covid or whether it’s the planetary health crisis that we are facing today, so scientists must have a seat at the table, because they can guide good decision-making. The second one is to showcase that there is a very simple way, a very cost-effective way, to accelerate innovation and economic growth, and that is to make the science openly accessible. If we do that scientists can build so much faster, whether they sit in Africa or Harvard or MIT or somewhere in Europe, it doesn’t matter. Everybody profits and benefits from science made openly accessible.

This article is content that would normally only be available to subscribers. Become a subscriber to see what you have been missing