A digitally-optimized logistics industry could add huge value to the world economy.

From the time a product leaves a factory in some distant corner of the world to the moment it reaches your doorstep, it uses a dizzying number of services, with dozens of companies exchanging hundreds of different data points. It is a remarkable journey made even more epic by the fact that so many logistics services remain in a digital dark age, completing transactions via phone, paper and fax machine.

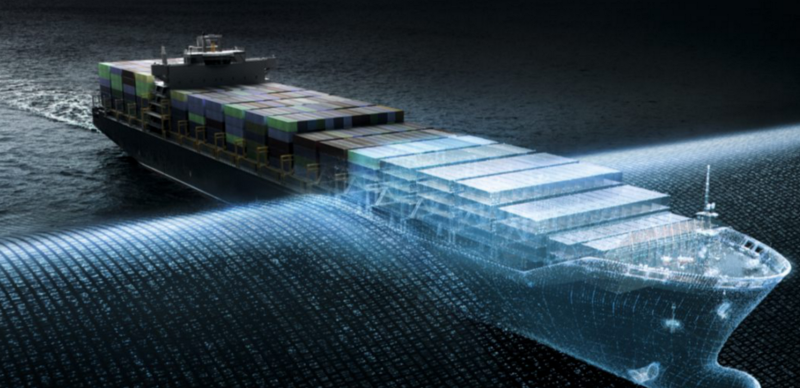

No wonder logistics companies are being targeted from all sides for massive disruption. Startups as well as some of the world’s biggest corporates are marshalling financial and technical resources to transform logistics through the use of autonomous cargo ships, Uber-like shipping platforms, artificial intelligence-driven warehouses, delivery drones and modular self-driving delivery vehicles.

These sweeping efforts have the potential to accelerate the delivery of just about every good, reduce delivery times, shrink costs, and eliminate waste. Yet this momentum is being sapped by a vast legacy infrastructure that is so antiquated that it’s hard for companies to transition into this new world. The challenge for participants in the logistics revolution is to get all the pieces to align to deliver the promised benefits.

The World Economic Forum estimates that an average of 85 million packages or documents are shipped every day. The system is coming under strain as fuel prices rise and consumers come to expect fast delivery of any product at any time. This requires a flexibility and agility that is simply impossible for many logistics players, according to a recent study co-authored by Shanton Wilcox, Partner & Manufacturing Segment Head for Infosys Consulting. Most shippers understand the need for agility but, the report says, 42% haven’t made changes in the past five years. “A lot of the basics are broken, and the foundation is just not there to allow them to get where they want to be,” Wilcox says. Frustrated by the slow pace of change, e-commerce giant Amazon has registered itself as a freight forwarder, allowing it to help partners manage the regulations and logistics associated with international shipping. The company is also experimenting with things like an on-demand delivery service dubbed “Amazon Flex,” an Amazon Air fleet of planes, and a Delivery Service Partner program for franchise delivery businesses. It has also built 744 operational facilities around the world and ordered 20,000 Mercedes-Benz vans that it plans to use as part of a leasing program targeting small businesses.

Brian Solis, a principal analyst at the Altimeter research firm, says retailers and logistics players have no choice but to adapt. “You as a consumer are being constantly taught to expect immediacy and personalization,” Solis said. “You’re constantly wanting something more and faster and better. Everything is being reinvented to cater to this accidental narcissist. No matter what business you’re in, this is happening.”

The World Economic Forum has tried to sound the alarm, urging logistics companies to move faster or risk squandering a massive economic opportunity. With e-commerce penetration projected to grow from 7% in 2015 to 17% in 2025, the Forum says a digitally-optimized logistics industry could add $4 trillion in value to the world economy. “Logistics has introduced digital innovations at a slower pace than some other industries,” says a Forum report. “This slower rate…brings enormous risks that, if ignored, could be potentially catastrophic for even the biggest established players in the business.” Indeed, there is a growing list of new entrants in areas such as shipping, warehousing and delivery with big ambitions.

SHIPPING: Making it Easy, Transparent and Efficient

Israeli entrepreneur Zvi Schreiber got the idea to disrupt the world of international freight shipping when, as a manager of an electronics company, he spent days calling shipping agents, trying to get price quotes.

The experience inspired him to found Tel Aviv-based Freightos in 2012, which has since raised $92 million in venture capital. Its fundamental mission is to make freight booking as easy as ordering an Uber. But so few shippers have even basic digital tools that Freightos in 2013 launched AcceleRate, a cloud-based service that allowed freight companies to digitize and centralize their internal information. Since then Freightos has launched a marketplace that lets adopters share their prices and book services across the Web. Making booking faster and more transparent helps ensure capacity on ships is being efficiently used, Schreiber says.

Rather than try to draw industry players into the modern world, Berlin- based FreightHub became a freight forwarder itself and entered directly into the business of shipping. Via its Web-based platform, customers — including small and medium-sized businesses — can book shipping. FreightHub, which has raised $23 million in venture capital, helps arrange the entire process through a network of agents, says CEO and co-founder Ferry Heilemann. Other startups such as Flexport, which has raised $300 million, and Fleet, are also entering the freight forwarding business. “People think it’s too complicated and that startups can’t tackle that,” says Heilemann, a scheduled speaker at Founders Forum x Industry in Partnership with Henkel conference in Dusseldorf, November 7–9. “But that’s what they used to say about fintech startups and the financial industry.” Disruptions from startups are forcing stalwarts to adapt. Shipping giant Maersk’s freight-forwarding unit Damco launched a digital platform last year called “Twille” Likewise, freight forwarder DHL earlier this year released MySupplyChain, a software and service designed to allow for greater tracking of shipments as well as enhanced data analytics. Even vessels are getting an overhaul. U.K.-based Rolls-Royce is developing autonomous and remote-controlled cargo ships that it hopes to deploy by 2025. The autonomous system is being developed at the company’s R&D centers in Finland and Norway. According to the United Nations, about 90% of the world’s trade is carried over the seas, and Rolls-Royce believes autonomous fleets of ships can increase safety and efficiency.

“We’ve proven a lot of the technology that’s required,” says Kevin Daffey, Director of Engineering, Technology and Ship Intelligence at Rolls-Royce. “Now it’s about convincing businesses that there’s a business case and that it can revolutionize their business model.”

Still, it’s an enormous undertaking to equip ships with the array of visual sensors and cameras needed, plus the servers necessary to process the data in real-time, which could be as much as one terabyte per day per ship.

WAREHOUSES: From Clunky To Instant Fulfillment

Once merchandise clears a port, it is almost guaranteed to pass through one or more warehouses as it winds its way to a home or business. The traditional, clunky methods of inventory distribution, fulfillment, and preparation for delivery create another painful bottleneck.

Traditional players are taking steps to change that. For example, United Parcel Service has announced it is developing an analytics and machine learning project to better leverage the vast amounts of data it generates to create better predictive tools and better manage storage and capacity across its warehouses and vehicle fleets. And, to remain competitive, French retailer Cdiscount, founded almost 20 years ago in Bordeaux, created its own in- house lab called “The Warehouse.” It brings in startups that can help it make better use of data and robotics in its warehouses, better manage peak sales cycles and improve delivery via technologies such as autonomous vehicles. For companies who don’t have the resources or expertise Mumbai-based Fractal Analytics has developed algorithms and artificial intelligence to more accurately predict inventory needs and management. In one case, a customer was able to save $5 million by reducing the inventory it kept on hand, says the company. That kind of smarter fulfillment also allows such warehouses to be more responsive to on-demand orders.

Other startups are trying to reinvent the very concept of a warehouse. Israel’s Commonsense Robotics just recently launched a 6,000 square-foot micro-fulfillment center in downtown Tel Aviv that provides autonomous sorting and shipping. Using a mix of robotics, AI and humans, the company can more efficiently use its tiny warehouse to deliver goods in city centers. Chaldal is going one step further, by using robotics and AI to create networks of single room “nano-warehouses” in crowded developing cities like Dhaka, Bangladesh, where it is based, to do on-demand fulfillment. And Austria- based Logsta launched last year to create warehouses that are at the center of a service that helps small businesses with everything from learning how to get their products into Web-based marketplaces like Amazon to helping arrange all aspects of shipping and last-mile delivery.

Transforming warehouses is critical for businesses to stay competitive as last-mile delivery options explode. In the U.S. alone companies like grocery- delivery service Instacart, which just raised $600 million in venture capital, and Postmates, which now offers delivery of food and goods in 550 cities, are making instant fulfillment the default expectation.

Transforming the Last Mile

For many consumers, much of the logistics revolution looks like a young college student furiously pedaling a bicycle around city streets carrying a larger Deliveroo or Uber Eats insulated backpack. While this analog solution is indeed fueling an ecommerce expansion, the mobility industry has far more ambitious plans to reimagine this end of logistics.

Amazon has been experimenting with drone technology, as has China’s JD.com, which has been delivering small packages to remote areas. Meanwhile, Israel’s Flytrex struck a drone delivery partnership with Icelandic ecommerce startup AHA in August 2017. Mostly, the packages tend to be smaller goods, like food, or new smartphones. Currently, AHA is approved to fly 13 routes around Reykjavik.

But drones are still often limited to one item under a certain size. A wide range of automotive makers believe they can have an even bigger impact on logistics by introducing fleets of self-driving trucks for long-haul shipping and autonomous vans for last-mile deliveries. Volvo Trucks recently introduced Vera, a self-driving truck concept for well-defined routes in limited spaces such as ports or warehouse districts that could carry freight. Vera is a truck tractor that can pull a trailer but has no cab for a human. Mercedes-Benz Vans is taking a hybrid strategy, creating a self-driving platform called “Vision URBANETIC” that offers one module for carrying people and another that can hold ten pallets of goods. Renault, meanwhile is developing its own modular, self-driving delivery pod called “EZ-Pro.” These can be reconfigured with different pods and run separately, or in a platoon. In some cases, a human could ride along to carry the packages from the pod to the customer. Startups are also targeting the opportunity. According to CB Insights, trucking- related startups raised more than $1 billion in 2017, up from the $763 million invested in 2016. Each of these investments is building toward the larger logistics revolution by creating delivery networks that will expand the types of goods merchants can send on-demand, says Paul Asel, a managing partner at Nokia Growth Partners in San Francisco, which has invested in Peloton, a startup developing autonomous systems for long-haul trucks. As more vehicles become autonomous, and more inefficiencies are eliminated across logistics, consumers will reap enormous benefits.

“We believe as the marginal cost of delivering goods and services declines, there will be a lot more services that people choose to use in terms of last- mile delivery,” Asel says, “As soon as you start thinking through the ripple effect of this, it really becomes exciting.”